Reading Wittgenstein Between the Texts

¶ 1 Leave a comment on paragraph 1 0 This post is the fourth of a series of contributions to the DR2 Conference.

¶ 2 Leave a comment on paragraph 2 0 Comments are welcome! (How to comment)

Marco santoro1, massimo airoldi2 & Emanuela riviera3

¶ 3 Leave a comment on paragraph 3 0 1 University of Bologna; 2 University of EM, Lyon; 3 Independent Researcher

¶ 4 Leave a comment on paragraph 4 0

¶ 5 Leave a comment on paragraph 5 0 ABSTRACT: Sharing the “historicist challenge to analytic philosophy” (Glock 2006) we attempt a “distant reading” of the (mainly) philosophical literature on and about Ludwig Wittgenstein. We start with a descriptive profile of the temporal structure of LW’s work. Then we focus on the literature (i.e. scholarship) on LW as we have been able to represent it through an analysis of bibliographic data drawn from the Philosopher’s Index, an electronic bibliographic database especially devoted to philosophy as a discipline. This is the central section of our paper, and the longer one, in which we attempt to describe and to map with the help of more sophisticated statistical tools Wittgenstein scholarship in its properties and changing forms. We look at the social profile and relations of the authors who contributes to the establishment of LW as a central reference in the current intellectual landscape as well as the network and dynamics of topics to which LW has been associated. We end by proposing a set of possible explanatory frameworks (not really explanations, but research directions for elaborating explanations) for our results. With our paper we would add a “social dimension” to the aforementioned historicist challenge, making a case for an historical-sociological approach to (analytic) philosophy, along the lines of Bourdieu (1988) on Heidegger, Lamont (1992) on Derrida, Gross (2006) on Rorty, and Collins (1999) on the whole philosophical tradition.

¶ 6 Leave a comment on paragraph 6 0

¶ 7 Leave a comment on paragraph 7 0 My work consists of two parts:

¶ 8 Leave a comment on paragraph 8 0 the one presented here plus all that I have not written

¶ 9 Leave a comment on paragraph 9 0 (L. Wittgenstein)

¶ 10 Leave a comment on paragraph 10 0

¶ 11 Leave a comment on paragraph 11 0 In this paper we will attempt a “distant reading”[1] of the (mainly) philosophical literature on and about Ludwig Wittgenstein (LW). We are not doing research on Wittgenstein’s work as such but on people doing research on him. This is one first sense according to which we understand the meaning of ‘distance’ in our ‘distant reading.’ The second sense is that we are not studying those people through a close reading of their texts, but through a reconstruction of the aggregate properties of their works and of themselves as authors. Indeed, it is a sociology of philosophical work addressed from the vantage point of its output, a bibliography, what we are attempting here[2]. The choice of LW as the main reference of our research has two reasons. First, he is “considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century” (Stanford Philosophical Encyclopedia) or at least “one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century” (Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy -IEP)[3]. At least two major traditions of philosophical research have elected him as a central reference point, i.e. logic positivism and later analytic philosophy (see e.g. Gellner 1958; Hacker 1996; Tripodi 2015), not to mention more specialized fields as the philosophy of language, the philosophy of mathematics and the philosophy of mind. A focus on him has therefore an intrinsic interest even if it would make a case less generalizable than other, less influential and more “typical” philosophers (if such a figure ever exists). Second, as social scientists we have a special interest in Wittgenstein as possibly the most “sociologically relevant” of contemporary philosophers, or at least the philosopher whose work has exerted the stronger impact on the social sciences – sociology as well as anthropology (Winch 1959; Saran 1965; Giddens 1976; Porpora 1983; Bloor 1997; Das 1998; Pleasants 2002; Rawls 2008) and to a lesser extent even political science (Pitkin 1972). Currently, LW is still a major influence over at least three influential research streams in social theory, namely the sociology of scientific knowledge, ethnomethodology, and practice theory (e.g. Bloor 1973, 1983; Phillips 1977; Coulter 1979; Lynch 1992, 1993; Schusterman 1998; Schatzki et al 2001; Stern 2002; Kusch 2004; Bernasconi-Kohn 2007; Sharrock, Hughes, and Anderson 2013). Indeed, LW’s influence in a growing number of fields outside philosophy is what observers (including historians of contemporary philosophy) suggest[4] and it is what our research aims to assess empirically.

¶ 12 Leave a comment on paragraph 12 0 There is indeed a third reason for our choice of LW: the richness and complexity of his publishing and editing history (Kenny 2005; Erbacher 2015), which makes “Wittgenstein” a strategic case study for a research on cultural production and postmortem consecration – two major topics in the contemporary sociology of cultural life (see for instance Heinich 1990; Santoro 2010; Fine 2012). Indeed, this third reason crisscrosses profitably with the first, when considering that Wittgenstein’s stardom in the philosophical field has grown along with the posthumous publications of his (many) unpublished writings, and that LW’s place in contemporary analytic philosophy has considerably declined in the last decades – or at least this is what the now standard tale tells us (Hacker 1996; Tripodi 2009).

¶ 13 Leave a comment on paragraph 13 0 We have organized our paper in three virtual sections. First, we describe the temporal structure of LW’s work: to have a literature on Wittgenstein you need to have Wittgenstein’s literature, so it seems necessary to have at least some knowledge of the latter. Second, we focus on the literature (i.e. scholarship) on LW as we have been able to represent it through an analysis of bibliographic data drawn from the Philosopher’s Index, an electronic bibliographic database especially devoted to philosophy as a discipline. This is the central section of our paper, and the longer one, in which we attempt to describe and to map with the help of a few sophisticated statistical tools Wittgensteinian scholarship in its properties and changing forms. Third, we set forth a series of provisional explanations for our results, also considering the research on Wittgenstein beyond and besides the philosophical field, looking for trends and patterns of circulation of his ideas across different research areas and disciplinary fields, mapping what we would call, following Bourdieu (2002), the ‘international field of Wittgensteinism’.[5]. In particular, we advance four hypothesis, mutually compatible and reinforcing, two referring to exogenous and two to endogenous explanations in the sociology of cultural life (Kaufman 2004), which we suggest could be used to make sense of the results of our distant reading.

¶ 14 Leave a comment on paragraph 14 0

1. The structure of LW’s work and the philosophical field.

¶ 15 Leave a comment on paragraph 15 0 Far from being a strange one, the question “What is a work by Wittgenstein?“ (Schulte 2006) is not only appropriate: it is almost inevitable in a research as ours. The literature on LW is chronologically intermeshed with Wittgenstein’s philosophical work as it was made available to readers and authors, in a relation that is circular: research on LW – secondary literature as it is called – has been part and parcel with the same work for which LW is acknowledged as author. As Wittgenstein published barely 25,000 words of philosophical writing during his lifetime— including a book (i.e. the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus), a caustic book review, and a very short conference paper he never read—the texts or writings that he left unpublished have played an unusually large role in the reception of his work – comparable probably in 20th century to Husserl and Gramsci only.

¶ 16 Leave a comment on paragraph 16 0 According to public estimates, the posthumous publications, almost all of them based on materials collected in his Nachlass, contain well over a million words. As the Nachlass as a whole contains approximately three million words (i.e. over 20,000 pages of manuscripts and typescripts), one might estimate that roughly a third of Wittgenstein’s writing is in print. However, as much of the material that was not edited for publication consists of early versions, rearrangements, and other source material for the previously published material, one could argue that considerably less than two thirds of his Nachlass has still to see the light of day in one form or another.

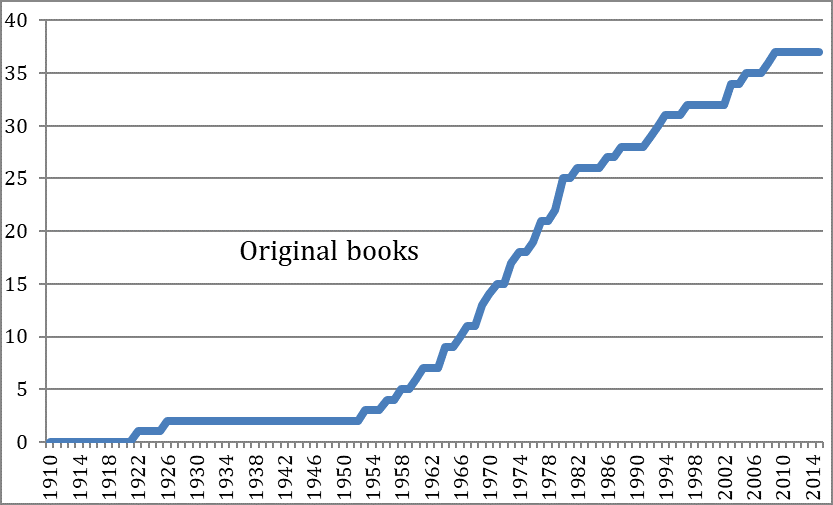

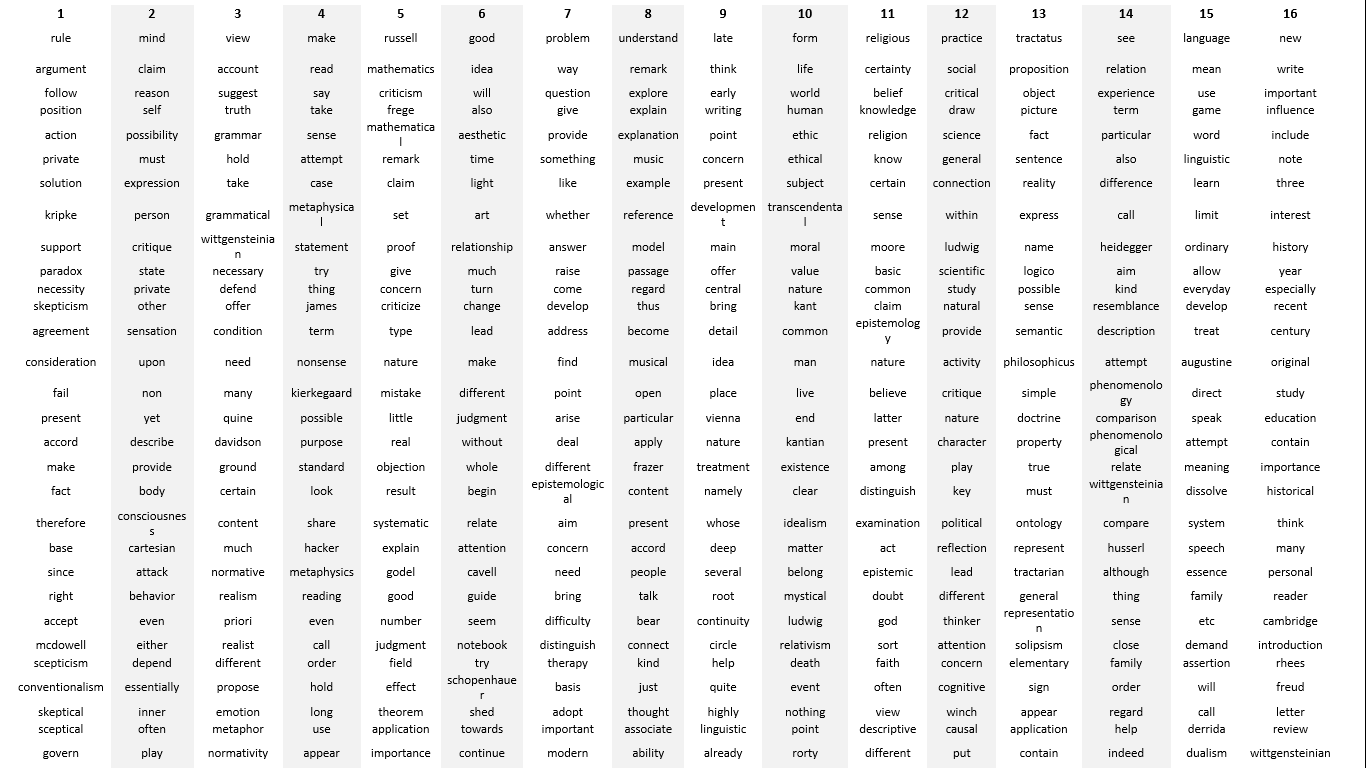

¶ 17 Leave a comment on paragraph 17 0 Fig. 1 – The temporal structure of LW’s work

¶ 18 Leave a comment on paragraph 18 0 Legenda: new edition/translation only in English

¶ 19

Leave a comment on paragraph 19 1

¶ 20 Leave a comment on paragraph 20 0 Fig. 2. A cumulative work, in published books (1922-2015)

¶ 21 Leave a comment on paragraph 21 0

¶ 22 Leave a comment on paragraph 22 1 The publishing history of LW is however less linear than it may appear from these figures. Consider the following. As Wittgenstein never copyedited any of these papers for publication, each of the posthumous books and papers called for substantial editorial decisions about their content, and how to present it; b) three persons (G.E.M. Ascombe, R. Rhees and G.H. von Wright) have been charged by the same LW of these publications after LW’s death, and they had to negotiate among themselves and other actors (e.g. publishing houses, other people owning materials etc.) exactly what to publish and in which order and form; c) very soon other people entered in the business, more or less accepted by the literary heirs, who made what was possible to them to keep control over the publication plans; d) new materials (manuscripts, letters, lessons’ transcriptions) have come to light, or to the market; e) manuscripts and typescripts had usually to be translated from their original German, and this asked for a preliminary interpretation and opened the door to “manipulation”, also in a positive sense; f) new collective actors entered the game time after time, as departments (e.g. Cornell’s Dept. of Philosophy who owned a copy of all the materials, Bergen’s Dept. who bought these copies in order to digitalize it, etc.); g) editing conventions as well as publishing technologies have been changing, asking for new editions and new solutions.

¶ 23 Leave a comment on paragraph 23 0 Consequently, almost all of the twentieth-century publications from the Nachlass were extensively edited, often with little or no indication of the relationship between the source texts and the published material (at least till what Erbacher calls the “later rounds of editing Wittgenstein’s Nachlass”), opening the door to debate about not only the content of LW’s ideas but also their form, composition and structure. Briefly, the Work was far from being fixed, established, crystallized, and not only its contents but also its forms and its boundaries have been themselves a stake in the politico-intellectual game through which Wittgenstein as both an Author and a Person has been known (i.e. read, commented, criticised, contradicted, supported, refined, developed, interpreted, canonized etc.) in the almost seven decades after his death.[6] In a sense, LW’s work – once published – has fostered if not generated what LW has tried to fight if not solve all his life: “philosophical problems”. To be sure, this generation started in 1922 (the year of publication of the Tractatus) but has literally exploded only after 1953 (the year of the posthumous publication of the Untersuchungen/Investigations, that is the first of his post-mortem books and for many still his masterpiece).

¶ 24 Leave a comment on paragraph 24 0 As we will show, LW work has spurred a whole “industry” inside the philosophical discipline, an industry made of people, articles, books, journals, conferences, associations, academic positions, fellowships, and so on. Our research focuses on this industry – that we would conceptualize, following Pierre Bourdieu’s sociological theory, as a field of cultural production (or better: as a subfield located at the intersection of other fields, including the field of philosophy as an academic discipline):

¶ 25 Leave a comment on paragraph 25 0 The space of literary or artistic position-takings, i.e. the structured set of the manifestations of the social agents involved in the field — literary or artistic works, of course, but also political acts or pronouncements, manifestos or polemics, etc. — is inseparable from the space of literary or artistic positions defined by possession of a determinate quantity of specific capital (recognition) and, at the same time, by occupation of a determinate position in the structure of the distribution of this specific capital. The literary or artistic field is a field of forces, but it is also a field of struggles tending to transform or conserve this field of forces. It follows from this, for example, that a position-taking changes, even when the position remains identical, whenever there is change in the universe of options that are simultaneously offered for producers and consumers to choose from. The meaning of a work (artistic, literary, philosophical, etc.) changes automatically with each change in the field within which it is situated for the spectator or reader (Bourdieu 1993, p. 30).

¶ 26 Leave a comment on paragraph 26 1 Fundamental to Bourdieu’s view is that we cannot understand any work of philosophy (or art, literature and science, by implication) purely in reference to itself. Rather, it is necessary to situate the work in terms of other points of reference in meaning and practice. So he writes that we cannot understand the history of philosophy as a grand summit conference among the great philosophers (p. 32); instead, it is necessary to situate e.g. Descartes within his specific intellectual and practical context, and likewise Leibniz as any other. And the meaning of the work changes as its points of reference shift. This fact of relationality and embeddedness raises serious issues of interpretation for later readers. As Bourdieu observes:

¶ 27 Leave a comment on paragraph 27 0 One of the major difficulties of the social history of philosophy, art or literature is that it has to reconstruct these spaces of original possibles which, because they were part of the self-evident givens of the situation, remained unremarked and are therefore unlikely to be mentioned in contemporary accounts, chronicles or memoirs…In fact, what circulates between contemporary philosophers, or those of different epochs, are not only canonical texts, but a whole philosophical doxa carried along by intellectual rumour — labels of schools, truncated quotations, functioning as slogans in celebration or polemics — by academic routine and perhaps above all by school manuals (an unmentionable reference), which perhaps do more than anything else to constitute the ‘common sense’ of an intellectual generation. (1993, pp. 31-32).

¶ 28 Leave a comment on paragraph 28 0 This background information is not merely semiotic; it is institutional and material as well. It includes “information about institutions — e.g. academies, journals, magazines, galleries, publishers, etc. — and about persons, their relationships, liaisons and quarrels, information about the ideas and problems which are ‘in the air’ and circulate orally in gossip and rumour” (1993, p. 32). So the intellectual product is created by the author; but also by the field of knowledge and institutions into which it is offered[7].

¶ 29 Leave a comment on paragraph 29 0 In the following pages we will attempt a description of what we would call the “Wittgenstenian field”. This is just a first assessment of a more complex social and intellectual world (an “intellectual microcosm”, we could say still following Bourdieu), whose boundaries, dimensions, and axes of structuration ask for a deeper investigation and a wider set of sources and data. This said, we believe we can provide a first assessment of this field moving from a methodical selection and analysis of information available in some established bibliographical sources.

¶ 30 Leave a comment on paragraph 30 0

- ¶ 31 Leave a comment on paragraph 31 0

-

Sources and data

¶ 32 Leave a comment on paragraph 32 0 In order to assess volume and structure of the (so called ‘secondary’) literature produced on LW – in more sociological terms, the more visible, superficial aspect of what we have named the “Wittgensteinian field” – we have built a set of data drawn from the Philosopher’s Index, a specialised archive that is possibly the best available source for attempting a systematic analysis of the international literature in the current philosophical discipline (which is indeed more a series of philosophical subdisciplines than a single disciplinary formation). As the website states: “This premier bibliographic database is designed to help researchers easily find publications of interest in the field of philosophy. Serving philosophers worldwide, it contains over 650,000 records from publications that date back to 1902 and originate from 139 countries in 37 languages. This ready source of information covers all subject areas of philosophy and related disciplines.”[8]

¶ 33 Leave a comment on paragraph 33 0 From this archive we have selected ALL the records containing the tag ‘Wittgenstein’ in the camp TITLE, within a time span from 1951 to 2015[9]. The subdata set comprises 4209 records, which are our unities of analysis.

¶ 34 Leave a comment on paragraph 34 0 While The Philosopher’s Index claims to provide “comprehensive coverage”, including “articles from over 1,750 Journals and e-Journals, Books, e-Books, Dictionaries and Encyclopedias, Anthologies, Contributions to Anthologies, Book Reviews”, its coverage is inevitably biased against more peripheral publications and languages, Italian included. Not every philosophical journal published in the world may be indeed covered, and we may be sure that not all publishing catalogues are pre-screened by the PI editors who select items to be indexed. A more or less extensive amount of pertinent publications inevitably escapes the PI’s coverage.

¶ 35 Leave a comment on paragraph 35 1 This means our data set comprises at best a not random sample of documents relative to LW and the few other philosophers we have selected for comparison. A sample because of the inevitably incomplete nature of the original archive we are working with, but also because of the highly restrictive criteria we have used in selecting our units of analysis. It is apparent that an article or a book can deal with Foucault or Wittgenstein without naming them in the title. So, our data set is far from approaching the universe – what Franco Moretti aimed to reach while studying the Victorian novel for example, after a compilation of many disparate sources still available to the scholar (Moretti 2013). At the same time, we would argue that our criteria, exactly because they are so restrictive, may capture better than others what we are looking for, i.e. a sample of documents representing the public impact these authors had and still may have on the cultural production of fellow scholars authoring texts in professionally recognized venues (as academic journals and established book series)[10].

¶ 36 Leave a comment on paragraph 36 0 This sample however is also – and we need to acknowledge it since the start – a not random one, because of different degrees of coverage of journals and other texts published in different countries and languages. (We know for example that not all the Italian production on LW is included in our dataset.) This is a sure weakness of our data, and therefore of any analysis of them. Waiting for a better, wider, less biased coverage of the literature, it seems useful to attempt the kind of research we are pursuing, at least with methodological objectives.

¶ 37 Leave a comment on paragraph 37 0

- ¶ 38 Leave a comment on paragraph 38 0

-

The “Wittgenstein field”: a first assessment

¶ 39 Leave a comment on paragraph 39 0 Of course, the contents of a work (as an opus operatum) are inside the work, and wait for being discovered. This is the common wisdom in humanistic scholarship, deeply embedded in educational and research practices as well as in a wide array of institutions. But is it the only way to address philosophy as both a form of knowledge and a tradition of texts and ideas? In a sense, philosophy as a disciplinary practice is a struggle for determining the meanings of philosophical works, or works with philosophical potentialities (e.g. a film). Books like The Conflict of Interpretations (Ricoeur 1967) or still earlier The Contest of Faculties (Kant 1798) make this explicit since their titles[11]. Randall Collins has developed a whole “sociology of philosophies” moving from the simple idea that:

¶ 40 Leave a comment on paragraph 40 0 Intellectual life is first of all conflict and disagreement… the forefront where ideas are created has always been a discussion among oppositions… Not warring individuals but a small number of warring camps is the pattern of intellectual history. Conflict is the energy source of intellectual life , and conflict is limited by itself (Collins 1999, p. 1).

¶ 41 Leave a comment on paragraph 41 1 Wittgenstein himself moved in his early work from a critical engagement with two of his contemporaries (Frege and Russell), and all his philosophical work has been said to consist of “remarks”[12] sometimes explicitly against some other thinkers – from Augustine to Frazer – and more in general against any instance of dogmatism (Kuusela 2008). In LW’s words: “Philosophy is a battle against the bewitchment of our intelligence by means of language” (1953, p. 109). Indeed, LW was one of those scholars who rarely refer directly to other scholars – but this doesn’t mean other scholars are not present between the lines of his writings. Still, other scholars were present – even physically – while LW was developing his ideas: something his acknowledgments in canonical books as Philosophical Investigations testify. (This line of research – i.e. the collective nature of Wittgenstein’s creativity and the social basis of his intellectual production[13] – won’t be pursued here, being the object of a future paper).

¶ 42

Leave a comment on paragraph 42 0

What about the LW’s? It is well known LW himself was far from satisfied of the effects of his work, and he had very ambivalent feelings about the opportunity to establish something like a “school” (see e.g. Wittgenstein 1998). However, his impact on others was already apparent in the thirties as a teacher in Cambridge, and has only grown in the following years. Many things have been said and written about the influence LW’s ideas and style have exerted on contemporary philosophers (see e.g. Leinfellner et al. 1978; Hacker 1996; Marconi 1987), but one is sure: they have provided new opportunities and resources for intellectual production, in primis about himself and his work.

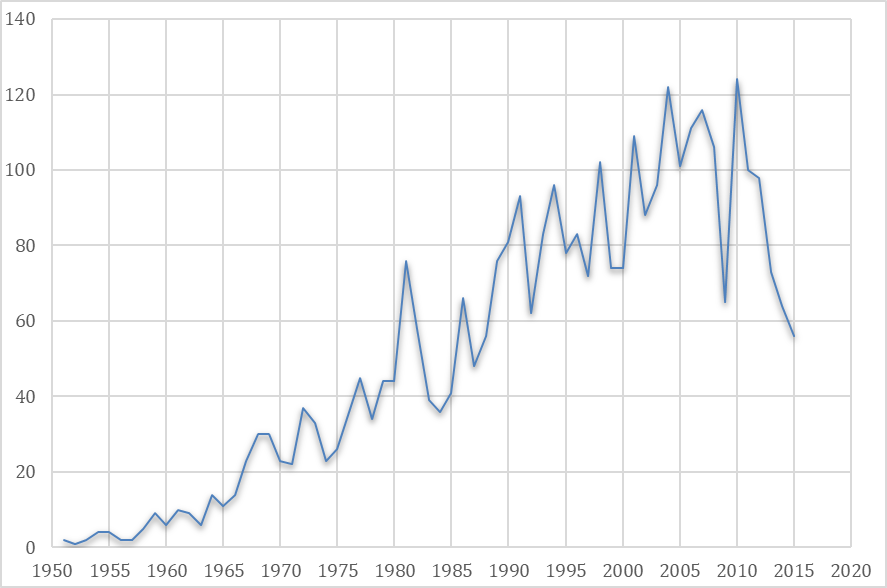

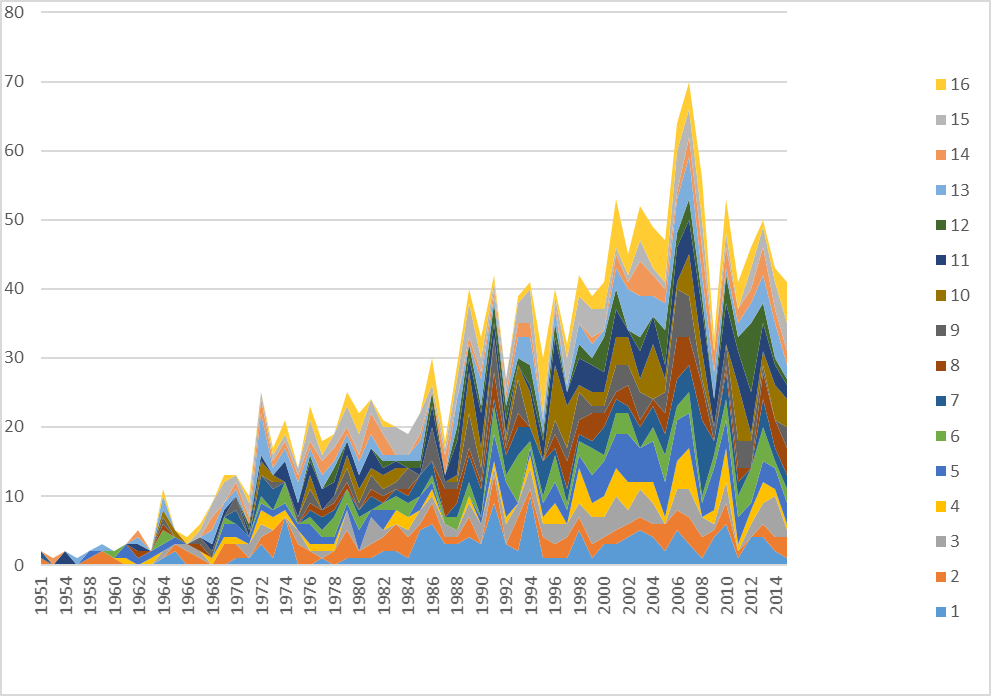

¶ 43 Leave a comment on paragraph 43 0 Fig. 2a. Publications on LW by year according to the PI, 1951-2015. Total frequencies.

¶ 44

Leave a comment on paragraph 44 0

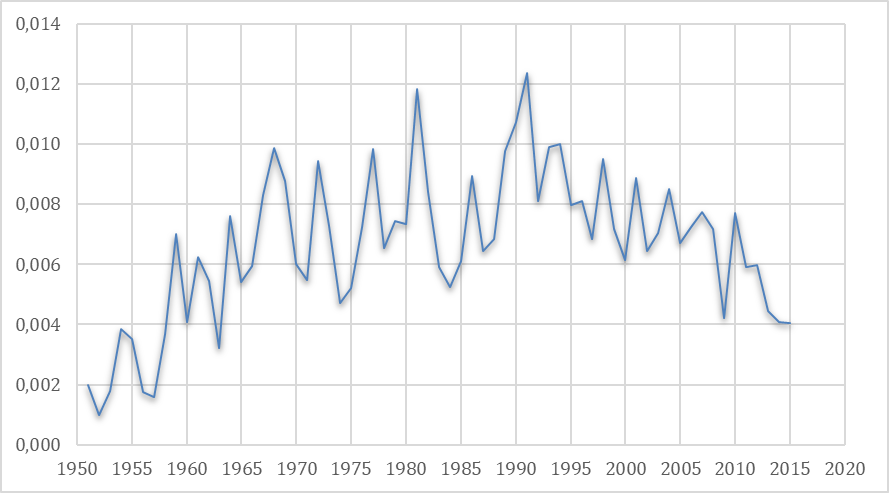

¶ 45 Leave a comment on paragraph 45 0 Fig. 2b. The same of 2a but “weighted” on total publications indexed in PI.

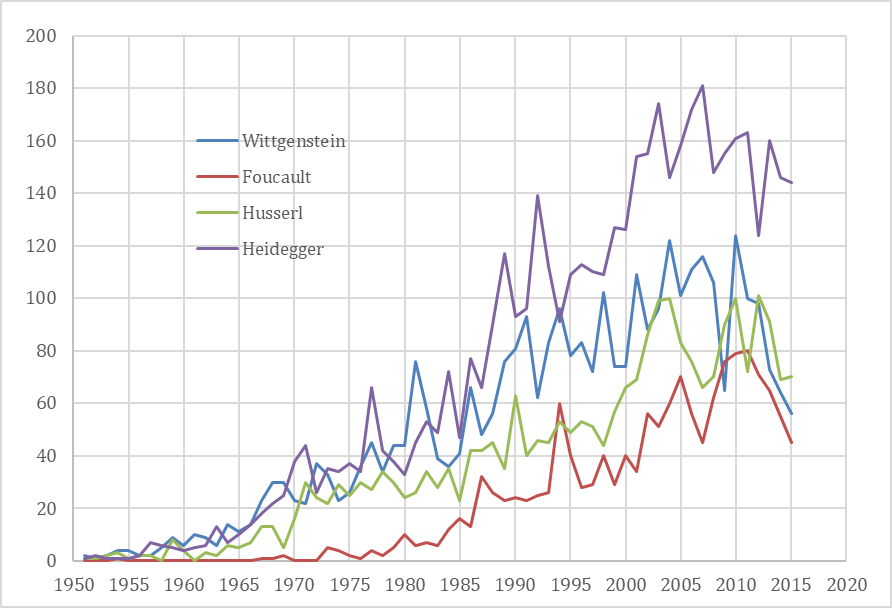

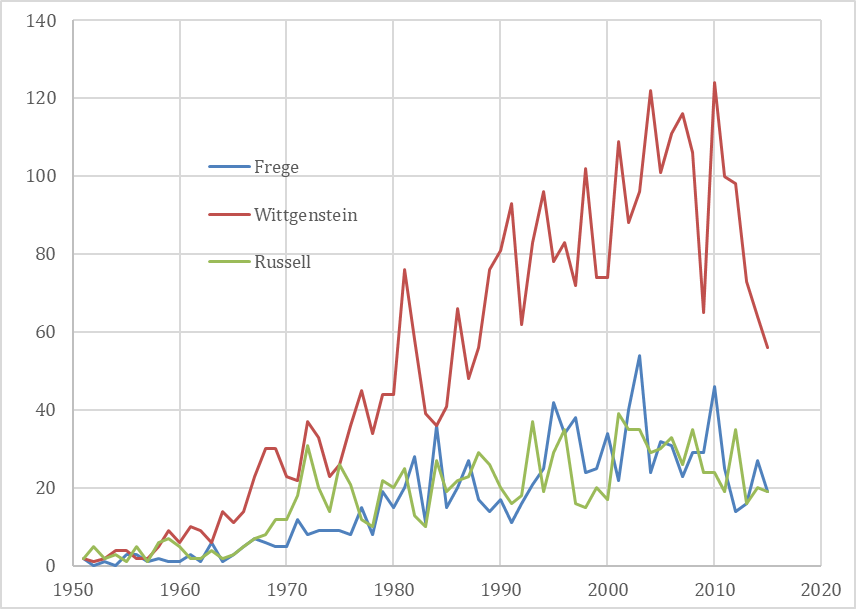

¶ 46 Leave a comment on paragraph 46 0 What the first figure shows is a rising trend till 2008 (and note the outburst in 1981), then an apparent fall in 2009, an highlight in 2010 and since then a continuous decline. But if we control data against the total of indexed publications (Fig 2b), the picture changes and takes the form of a parabola: an apparent growing trend till 1981 then a declining one interrupted only in 1991 (the climax of the whole series!) A better reading of these data asks for some comparison however. How strong is LW’s presence can be assessed only by way of a confrontation with other presumably influential authors. How voluminous is the production on LW with respect to the production of other “philosophical giants”? Is Wittgenstein a typical case or are there specific patterns in the history of his reception? Figures 3 and 4 offer some answers comparing trends of literary production on/about other five influential philosophers of the Twentieth century[14]: Husserl, Heidegger, Foucault (chosen as representatives of the so-called ‘continental philosophy tradition’) and Russell and Frege (selected as representatives of the so-called ‘analytic tradition’[15]). Only Heidegger among contemporary philosophers (i.e. philosophers active in the XX century) has spurred more discussion and intellectual production than Wittgenstein since the end of WWII. The intellectual productivity of LW ideas is dramatically apparent when compared to two of his main sources/influences[16], Bertrand Russell and Gottlob Frege (Figure 3).

¶ 47

Leave a comment on paragraph 47 0

¶ 48 Leave a comment on paragraph 48 0 Fig. 3. Literature on Wittgenstein, Foucault, Husserl and Heidegger compared, 1951-2015.

¶ 49 Leave a comment on paragraph 49 0 Source: our elaboration from Philosopher’s Index.

¶ 50

Leave a comment on paragraph 50 0

¶ 51 Leave a comment on paragraph 51 0 Fig. 4. Literature on Wittgenstein, Russell, Frege compared, 1951-2015.

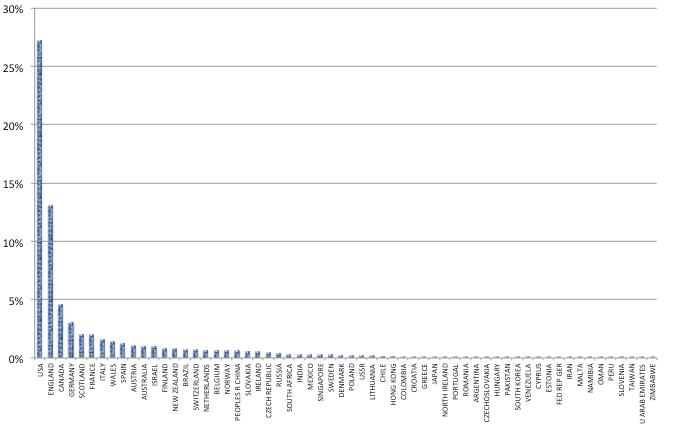

¶ 52 Leave a comment on paragraph 52 0 Source: our elaboration from Philosopher’s Index.

¶ 53 Leave a comment on paragraph 53 0

3.1. Some general properties of the “Wittgenstenian field”

¶ 54 Leave a comment on paragraph 54 0 Being LW our focus, the data we illustrate and discuss in the following of this paper are obviously limited to the ‘Wittgenstein’ subset. Some descriptive statistics will help to set the scene for the more sophisticated analysis we have conducted using bibliometric tools and topic modeling (on the latter see Mohr and Bogdanov, 2013).

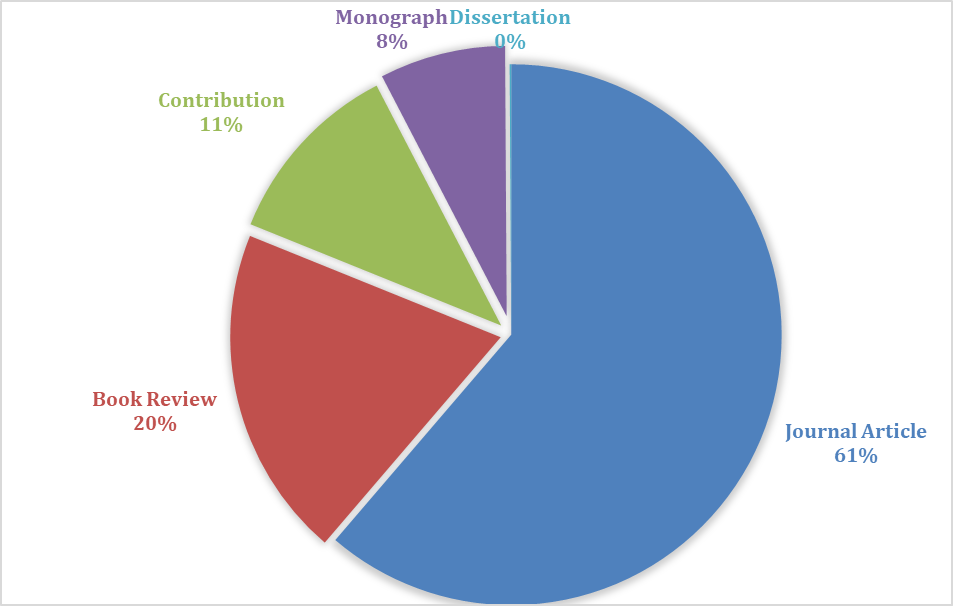

¶ 55 Leave a comment on paragraph 55 0 Tab 1 offers a first description of the subset according to different publication categories.[17] For our analysis we have selected a subsample excluding book reviews. The reason was both technical and substantive: PI uses different FORMS for book reviews, and the meaning of camps is different for them[18]. Substantively, we would say that book reviews are relative to the publication of books, which makes them redundant or a source of potential biases. The final, analysed data set comprises therefore 3374 records (77% are journal articles, 14% chapters in books and 9% books). The following tables and figures offer some useful information for characterizing the literature on LW along a series of relevant dimensions or variables – as language, venue of publication, publishers, authors, subjects (including comparisons or confrontations between LW and other authors).

¶ 56 Leave a comment on paragraph 56 0

¶ 57 Leave a comment on paragraph 57 2 Tab. 1. Records by publication type

| Publication type | N |

| Journal Article | 2579 |

| Book Review | 835 |

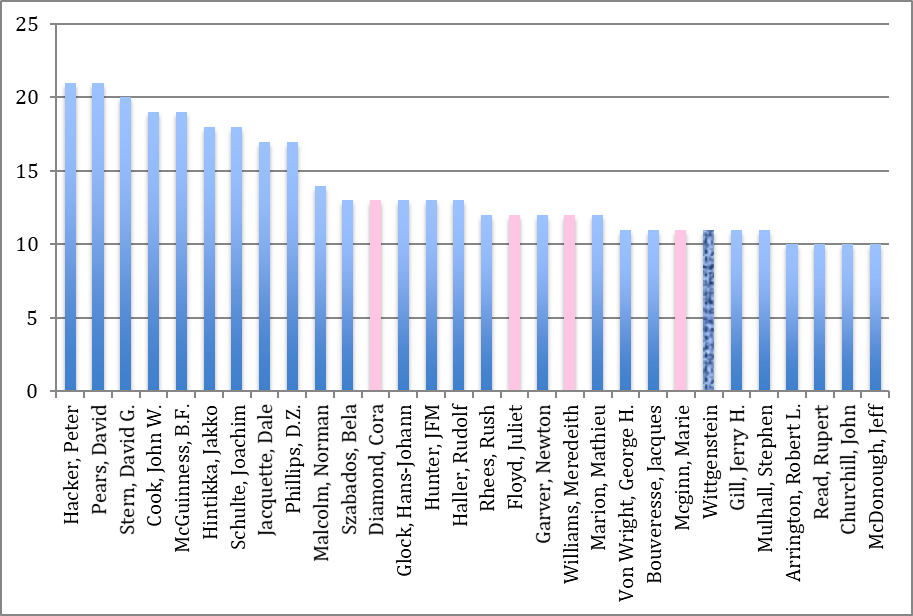

| Contribution in book | 474 |

| Monograph | 317 |

| Dissertation | 4 |

| Total | 4209 |

¶ 58 Leave a comment on paragraph 58 0 Source: Philosopher’s index, 1951-2015 (Tag ‘Wittgenstein’ in TITLE).

¶ 59 Leave a comment on paragraph 59 0

¶ 60

Leave a comment on paragraph 60 0

¶ 61 Leave a comment on paragraph 61 0 Fig. 5. Percentage distribution of records by publication type.

¶ 62

Leave a comment on paragraph 62 0

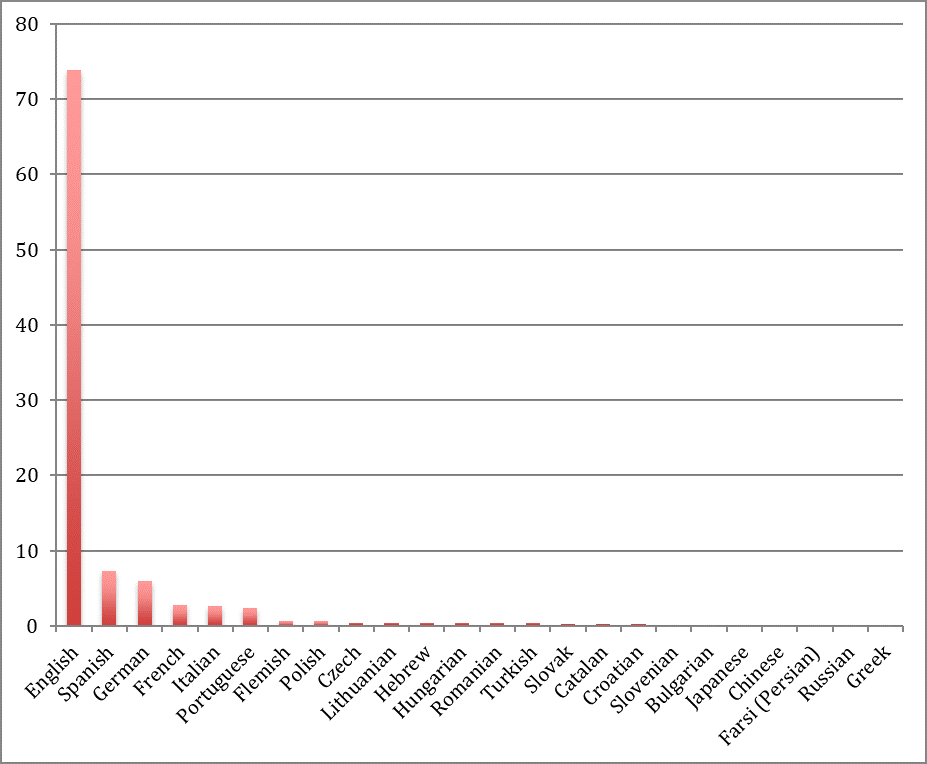

¶ 63 Leave a comment on paragraph 63 0 Fig. 6. Distribution of records by language (percentage).

¶ 64 Leave a comment on paragraph 64 3 English is clearly, and foreseeably, the language to which discussion on LW is preferably deferred and through which is mediated. This reflects both the dominance of this language in academic and scientific communication both the Anglophone horizon in which LW has worked in his professional life – but not in which he has originally thought and written. German is noteworthy third in this language ranking – much below English and even below Spanish (this Spanish literature on LW, accounting for 7,3% of the total and 247 titles, is something to be explored carefully, we suggest, much more than we can do here). Considering that LW was Austrian, that German was his mother tongue, and that almost everything written by LW available in English is also available in German, this gap is impressive. Of course, we are dealing with intellectual communities with different demographic sizes – the English being the natural language not only of British but also American scholars. But we have here also a clear reflection of the trajectory LW has followed after his death, and indeed even before it (recall he spent a few weeks in his last living years at Ithaca,, the small town where Cornell University is located, hosted by his ex student and pupil Norman Malcolm). It was through his American reception – mediated by Carnap and later Malcolm (Tripodi 2009) – that LW moved from the highly prestigious but relatively circumscribed British environment of Oxbridge to a global or globally relevant recognition, exactly in the same period in which American philosophy was gaining his worldwide primacy (Kuklick 2001).

¶ 65 Leave a comment on paragraph 65 0

3.2. Publishing venues

¶ 66 Leave a comment on paragraph 66 0 As emphasized by the sociology of science and knowledge (Boschetti 1985; Clemens et al 1995; Fleck et al 2018; Sapiro, Santoro, Beart 2019), journals like publishing houses play a central role in processes of reception and intellectual circulation, providing not only for material venues (the book as vehicle of texts and ideas) but also visibility and retrievability. In the case of LW’s writings there exists a long lasting pattern – Basil Blackwell as the main publisher for the English editions, and Suhrkamp for the German ones (with the main exception of the Tractatus, originally published in book form by Routledge).

¶ 67 Leave a comment on paragraph 67 1 What about texts not by LW but on him? Tabb. 2 and 3, referred respectively to journals and publishing houses, offer a rough description of the publishing structure of the Wittgenstenian literature, with interesting information about its institutional and geographical dimensions. First, as shown in Tab 2, there is great dispersion among many different journal sources (the total amounts to 616) with a limited number of records each (more than 250 have with just one publication on LW; average number of publications for source is 3,5). Second, there is an high concentration of records in just one source i.e. Philosophical Investigations, a quarterly peer reviewed journal established in 1978 with a wide scope and general aims (to publish articles on every field of philosophy) that has been however especially working as a receptacle for articles on LW. It seems to work like a “school journal”: it is indeed the official journal of the British Wittgenstein Society, a scholarly association founded in 2008 which is currently hosted by the University of Hertfordshire (UK).[19] Third, there are other, more specialised “sources” devoted to LW (e.g. the Nordic Wittgenstein Review-NWR, official journal of the Nordic Wittgenstein Society-NWS; or Wittgenstein Studies-WS, a series established in 2010 by the International Ludwig Wittgenstein Society and “designed as an annual forum for Wittgenstein research.” At present only two volumes) and it is notewhorty they don’t figure in this list (indeed they figure very low in the ranking, NWR at 448 and WS at 150). Fourth, Mind, the flag journal of Oxford-Cambridge philosophy (i.e. the philosophical tradition LW had the stronger impact in the fifties contributing to its same formation) is “only” at 12th position (but recall Mind is a long lasting journal, founded in 1876, and nowadays a reference journal for analytical philosophy and beyond).[20] Fifth, we should notice the fifth rank to a German-language (Austrian) journal: this seems important because it signals the persistence of a specifically Austrian tradition of philosophy claiming its special identity. Sixth, among the sources with at least 20 publications we find two Indian (i.e. not Western, even if linked to UK for historical reasons) ones, two from Israel, one Portuguese, one from Canada. Seventh, in the list we find a journal not specifically devoted to philosophy (Religious Studies).

¶ 68 Leave a comment on paragraph 68 0

¶ 69 Leave a comment on paragraph 69 1 Tab. 2. Distribution of records by source[21] (N=2990; reported only sources for 20+ occurrences).

| Source | N | % |

| Philosophical Investigations | 164 | 5,5 |

| Synthese. An International Journal for Epistemology, Methodology and Philosophy of Science | 53 | 1,8 |

| Philosophy. The Journal of the Royal Institute of Philosophy | 49 | 1,6 |

| Inquiry. An Interdisciplinary Journal of Philosophy | 40 | 1,3 |

| Grazer Philosophische Studien. Internationale Zeitschrift für Analytische Philosophie | 38 | 1,3 |

| Southern Journal Of Philosophy | 33 | 1,1 |

| Philosophical Quarterly | 32 | 1,1 |

| Indian Philosophical Quarterly | 31 | 1 |

| Dialogue. Canadian Philosophical Review | 31 | 1 |

| International Philosophical Quarterly | 29 | 1 |

| Philosophy And Phenomenological Research | 28 | 0,9 |

| Mind | 28 | 0,9 |

| Analysis And Metaphysics | 27 | 0,9 |

| Philosophy And Literature | 25 | 0,8 |

| Philosophical Review | 25 | 0,8 |

| Revue Internationale de Philosophie | 25 | 0,8 |

| Journal Of Indian Council Of Philosophical Research | 23 | 0,8 |

| Revista Portuguesa De Filosofia | 22 | 0,7 |

| Metaphilosophy | 22 | 0,7 |

| Deutsche Zeitschrift Für Philosophie | 21 | 0,7 |

| Philosophia. Philosophical Quarterly of Israel | 21 | 0,7 |

| Religious Studies | 20 | 0,7 |

| Iyyun. The Jerusalem Philosophical Quarterly | 20 | 0,7 |

| Philosophy Today | 20 | 0,7 |

| American Philosophical Quarterly | 20 | 0,7 |

| (…)

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 1 Total Sources (N=616) |

2290 |

¶ 70 Leave a comment on paragraph 70 1 Table 3 shows the distribution of publications on LW according to their publishers (data are referred to books and book chapters). Clearly, there is no strong correspondence between the structure of LW’s published work (mainly based on two publishers, Blackwell and Suhrkamp, as said) and the literature on him. With a 6% Wittgenstein’s main publisher Blackwell (in both the UK and US) features as fifth, after Routledge (an international group based in London), Cambridge UP and above all Rodopi (whose NL/USA branches account for 7,5% of the total) The German publisher of LW, Suhrkamp, is not a reference publisher for scholars working on LW. Oxford UP follows other publishers including Cambridge UP (5,1% including its division Clarendon). Anyway as Tab. 3 shows, the most frequent venue for scholars wanting to publish on LW in book format is a young German publishing house, Ontos Verlag, accounting for 13,6% of the total. Small, specialised publishers as Open Court, Thoemmes and Humanities Press are comparatively important venues. Stricto sensu “university presses” are a minority in the list – a datum difficult however to interpret as such (the point is: what about the literature on other philosophers? Is, e.g., is Heidegger a more established presence than Wittgenstein in the catalogues of university presses?). Relative to national distribution, beyond Anglo-American publishers, German language ones are well represented. Small countries as Norway and Netherlands, but even big countries not so central in the international philosophical establishment like Spain, figure in the top list.

¶ 71 Leave a comment on paragraph 71 0

¶ 72 Leave a comment on paragraph 72 1 Tab. 3. Publications by publishers (at least 10+).

| Publisher | N | % |

| Ontos Verlag (Germany)[22] | 108 | 13,6% |

| Rodopi (NL)[23] | 60 | 7,5% |

| Routledge (UK/International) | 59 | 7,4% |

| Cambridge Univ Press (UK) | 53 | 6,7% |

| Blackwell Publishing* (UK) | 48 | 6,0% |

| Holder-Pichler-Tempsky (Austria)[24] | 22 | 2,8% |

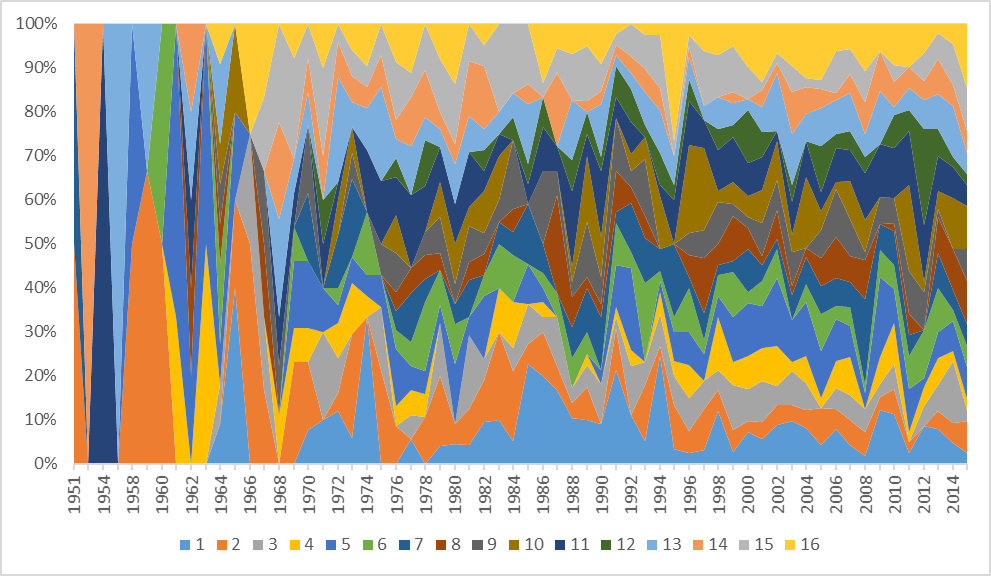

| Clarendon Press (Oxford, UK) | 21 | 2,6% |

| Oxford Univ Press (UK/International)) | 20 | 2,5% |

| Continuum International Publishing Group (USA)[25] | 18 | 2,3% |

| University of Chicago Press (USA) | 17 | 2,1% |

| De Gruyter (Germany) | 15 | 1,9% |

| Springer (Germany) | 15 | 1,9% |

| Garland (NY, USA)[26] | 14 | 1,8% |

| Ed Univ Castilla-La Mancha (Spain) | 14 | 1,8% |

| MIT Press (USA) | 13 | 1,6% |

| Rowman & Littlefield | 13 | 1,6% |

| Humanities Press (USA)[27] | 12 | 1,5% |

| Suny Press (USA) | 12 | 1,5% |

| Open Court (USA)[28] | 11 | 1,4% |

| Wittgenstein Archives (Bergen, Norway) | 11 | 1,4% |

| University Press of America (USA) | 10 | 1,3% |

| Thoemmes (UK)[29] | 10 | 1,3% |

| (…) | ||

| TOTAL | 795 | 100,0 |

¶ 73 Leave a comment on paragraph 73 0

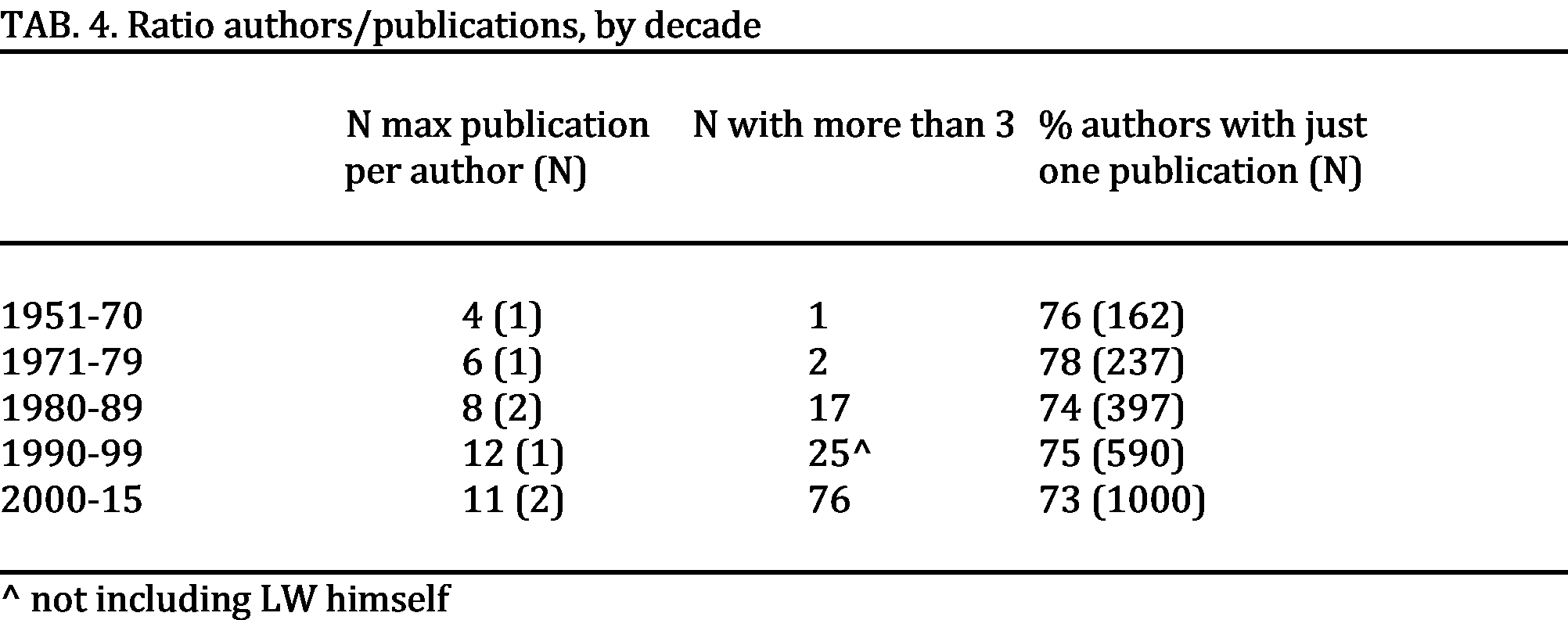

3.3. Who are the Wittgenstenians?

¶ 74 Leave a comment on paragraph 74 2 First of all, how many are they? Our dataset shows 1863 names, 1255 of which figure as author of just ONE publication (this means only 33% of the authors have written more than occasionally on LW). However, the general population tells less probably than the more restricted[30] set of highly specialised scholars from whom the bulk of the literature on LW comes. Suffice to say that thirty (i.e. 1.6%) have ten or more publications, accounting for 11.7% of the total number of publications (415 out of 3547). Their names (see Fig. 8) are familiar ones to scholars working on Wittgenstein but more in general on analytic philosophy and philosophical specialties as epistemology, logic, the philosophy of language, of mind but also ethics, aesthetics and even neurosciences. A few social properties of this more restricted population are apparent at first sight: it is predominantly male (there are just four women), white (no black, no coloured people), mainly located in the UK (at least eight) and the USA (at least 11) with just one Canadian, a few Continental Europeans (Germany, Austria, France, Hungary) and two Finnish. [31]

¶ 75

Leave a comment on paragraph 75 1

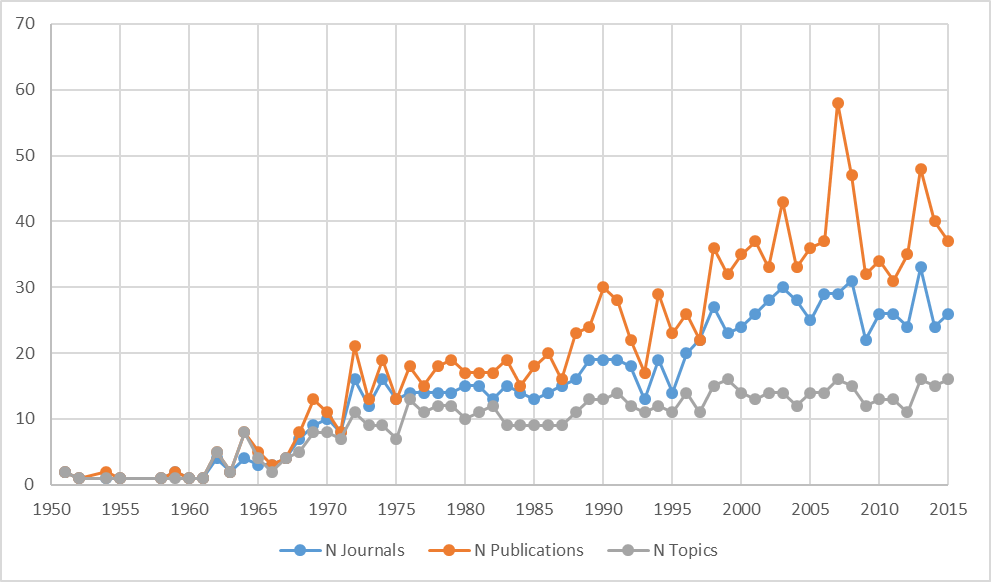

¶ 76 Leave a comment on paragraph 76 0 Fig. 7. Authors of publications on LW (at least 10).

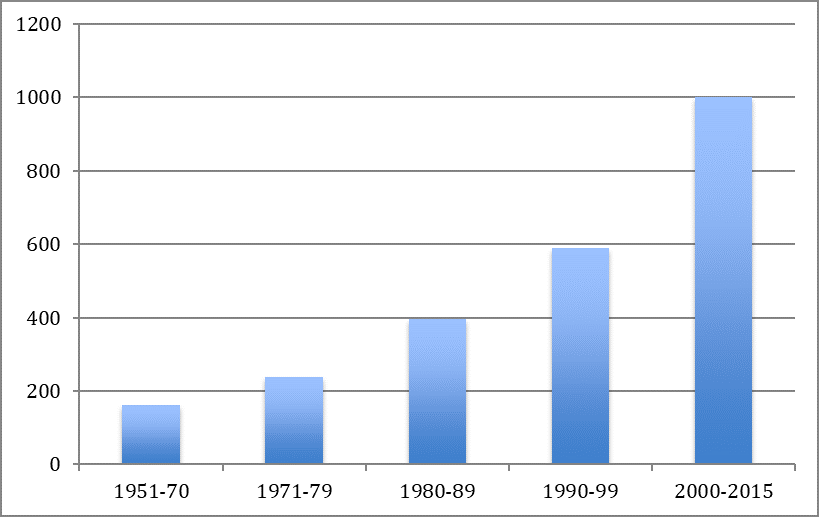

¶ 77 Leave a comment on paragraph 77 1 Names in figure 7 are representative of all the scholarship on LW since the Fifties, without distinctions for periods. So you can find authors born in the early 20th century and authors born in the sixties, dead authors and living authors, students of LW (as Malcolm or Rhees) and students of his students or friends (as Phillips or Hintikka). In other words, we need to break the whole set in periodical ones, as in Fig. 8. Looking at these data longitudinally you can have a sense of the growth of an industry – whose personnel are the authors working and publishing on LW (surely also as a function of the increase of active scholars in the academic system after the sixties, but we have no data at present to separate these two effects). The growth occurred is impressive, as the histograms show.

¶ 78

Leave a comment on paragraph 78 0

¶ 79 Leave a comment on paragraph 79 0 Fig. 8. Number of authors publishing on LW, by period.

¶ 80 Leave a comment on paragraph 80 1 Breaking the whole authors’ population for decades, a few patterns emerge along that of an evident growth. In the first period (two decades, 1951-70, N = 162) the more productive has just 4 publications (Engel), followed by 7 with 3 publications (among them von Wright, Moore, Rhees and Malcolm), 31 with 2 (including Hintikka and Winch) and 123 with just one publication. With the decade 1971-79 it is apparent a trend of increasing concentration and hyper-productivity among a few authors (the highest point is in the 1990-99 decade when a single author is responsible for 12 publications, i.e. Pearl). This pattern is accompanied by another one of stability, according to which the ratio of authors publishing just one text remains constant (around 15%) for more that six decades.

¶ 81

Leave a comment on paragraph 81 0

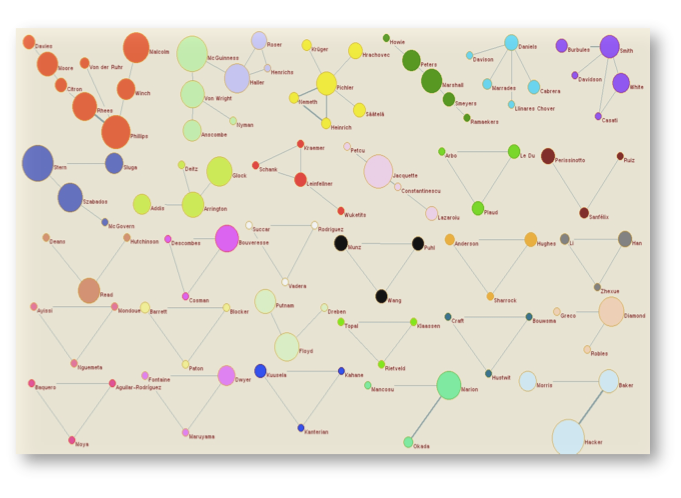

¶ 82 Leave a comment on paragraph 82 0 Some further information on the social structure of this intellectual microcosm is available in figure 9, where we diagrammatically represent the networks of co-authorship linking selected subsets of our population of Wittgensteinians. This is just an essay of a research line we are not pursuing in this paper but for which we would make a plea, i.e. the social network analysis of intellectual communities. The figure includes only systems of at least three linked authors (in other words, couples are not included in the figure). As the figure shows, the more common structure is the complete triad (three authors publishing together, or three couples). There are instances however of the so-called “impossible triad” (two couple of authors with one of them acting as just broker.) The largest network comprises seven nodes, including reference authors in this microcosm as Malcolm, Moore, Rhees, Winch, and Phillips. The rationale behind this kind of social analysis is that different network configurations account for different outcomes, as different arrangements of ideas or different rates of intellectual innovation (see Collins 1999; de Vaan et al 2015). We don’t pursue this investigative line in this paper however, and are happy just to suggest this research opportunity.

¶ 83

Leave a comment on paragraph 83 1

¶ 84 Leave a comment on paragraph 84 0 Fig. 9. Networks of co-authorship among authors publishing on LW.

¶ 85 Leave a comment on paragraph 85 0 Note: the size of the nodes is proportional to the number of publication ties.

¶ 86 Leave a comment on paragraph 86 0

- ¶ 87 Leave a comment on paragraph 87 0

-

Mapping subjects and modelling topics: the symbolic space of Wittgesteinism

4.1 A data-driven exploration

¶ 88 Leave a comment on paragraph 88 0 In the previous section we have attempted a sociological reconstruction of the Wittgenstenian research field since 1951 till 2015. We have identified a few social properties and some structural features, as well as some patterns of change as well as continuities. But we said nothing about the symbolic dimension of this field, i.e. about the identity and structure of the ideas circulating across this field. This is the objective of this section, where we show the main results of two distinct research paths.

¶ 89 Leave a comment on paragraph 89 0 The first has been aimed to identify the structure, borders and changes of the conceptual map beneath the intellectual production on LW: which themes, concerns, subjects scholars working on LW have understood as compelling and worth of their intellectual investments and efforts? How these concerns and subjects have changed across time? To answer to these questions we proceeded in two steps. First, we focused on the occurrence of ‘subjects’ (as reported in the PI)[32] identifying their ranking and temporal trends– at least for the most frequent ones. Second, we searched for relationships and forms. Methodologically, we have been looking for patterns of co-occurrence among (a) subjects and (b) words featuring in publications’ titles as well as in their abstracts[33]. The latter are distinctive means of scientific and academic communication – indeed, what distinguishes science (but for many verses also philosophy) from literature is also its literary form, including all those devices – like abstracts and keywords – developed to facilitate communication and exchange among scholars[34].

¶ 90 Leave a comment on paragraph 90 1 Abstracts are a great resource for any project of distant reading facilitating the processing of large texts (articles or chapters) through smaller ones (the abstracts). In fact, the second research path has been the application of so called “topic modelling” (TM) to this data set of abstracts in order to identify textual patterns beyond . TM is an increasingly popular statistical technique which allows the fast exploration of large amounts of text data (see Mohr and Bogdanov, 2013; see also Airoldi 2016 for an application to social media). In our study, we apply Latent Dirichlet Allocation (LDA) – that is, the most common and simple topic modeling algorithm (DiMaggio et al., 2013) – to the abstracts in English featured in our dataset (N = 1650). This technique has already been used for this purpose (McFarland et al., 2013; Jiang et al., 2016). In plain words, LDA discerns the semantic structure of a corpus of documents on the basis of patterns of word co-occurrences (DiMaggio et al., 2013). Its key assumption is that the analysed corpus of documents features a number k of distinct topics. In practice, the algorithm automatically identifies sets of words statistically associated to the k topics (each word can appear in more than one topic). Then, these coherent lists of words can be inspected and interpreted ex post. After having qualitatively inferred the semantic logic underlying each topic, it is possible to analyse topics’ distribution in the corpus and relate it to external variables. This has been done considering articles’ year of publication, as well as a field-level variable, that is, the number of different journals publishing about Wittgenstein each year.[35]

¶ 91 Leave a comment on paragraph 91 0 A methodological remark is in order at this point. To explore the ideational structure of a research field devoted to a scholar and her legacy, in our case LW, the best starting point would seem to have some knowledge about the contents and subjects of the scholar’s work. Which were LW’s main concerns and interests? Which topics did he address in his intellectual career? It is well known that there is not just one LW but (at least) two: the LW of the Tractatus and the LW of the Philosophical Investigations. Recently, this simple bipartition has been criticised, introducing a third, middle period, preparatory of the latter (Thompson 2008). We could certainly move from this picture (even the most sophisticated one) searching for its “reflection” in the literature on LW. But this would mean to reduce drastically the value and potentialities of our research methodology. Adopting a distant reading approach means to side step the results of previous (close) readings and to look for fresh information collected (but not immediately visible) in aggregate data. In other words, instead of searching in our data confirmation of what we already know, we should approach our data as original source of new knowledge (i.e. as data-driven research).

4.2 Mapping subjects

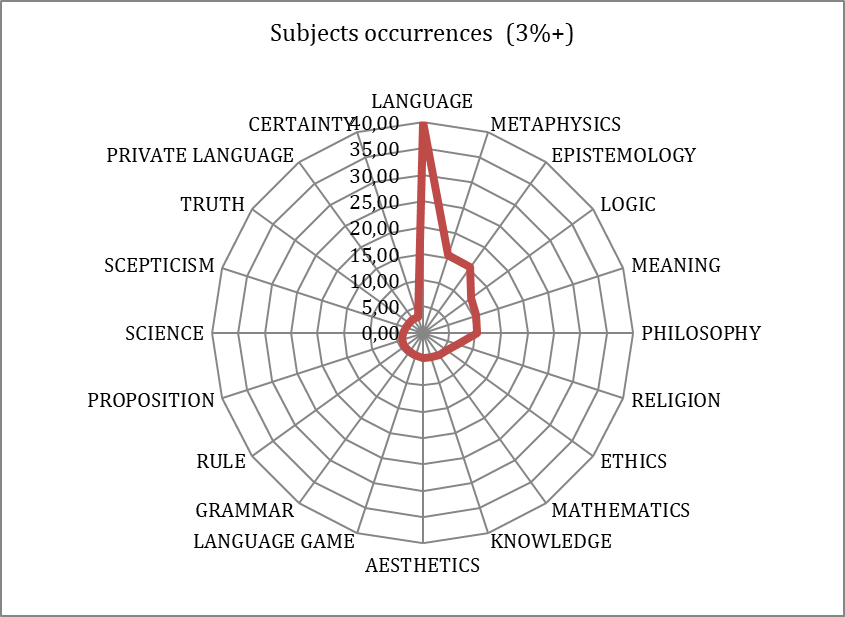

¶ 92 Leave a comment on paragraph 92 0 The number of recorded subjects included in our dataset is impressive[36]: we have collected 1.496 items for a total of 13.965 occurrences. As Fig 10 shows, the dispersion is only relatively high as the most frequent subject accounts for 40% of the total of the publications in our dataset, which seems a relatively high ratio.

¶ 93 Leave a comment on paragraph 93 0

¶ 94

Leave a comment on paragraph 94 0

¶ 95 Leave a comment on paragraph 95 0 Fig. 10. Subjects’ occurrences (% on the total records; min. 3%).

¶ 96 Leave a comment on paragraph 96 1 It comes as no surprise that this subject is LANGUAGE. Maybe more surprisingly, the second more frequent subject is METAPHYSICS (at 15,6%) – exactly the kind of intellectual endeavour Wittgenstein considered he was engaged against (but not really successfully, as many interpreters and critics have often noticed and our data indirectly confirm.) EPISTEMOLOGY, LOGIC, MEANINGS are what everyone with an even approximate knowledge of Wittgenstein may expect to find at this point. Less foreseeable are RELIGION and ETHICS – subjects about which there has been much attention in most recent years. Relatively low in raking are topics strongly associated with Wittgenstein and his thought – even his iconic image[37] – as RULE, LANGUAGE GAME, PRIVATE LANGUAGE and possibly PROPOSITION.

¶ 97 Leave a comment on paragraph 97 0 To go further in this exploration, fig. 12 maps subjects according to the strength of their relationships/associations (i.e. co-occurrence). The more associations a subject has with other subjects, the greater it features in the map (measure of “TOTAL LINK STRENGTH”). Subjects more frequently associated among themselves (which co-occur frequently in records) make a cluster, in the map identified with a certain colour (different colours make different clusters). Distance is relative to strength of association (closer co-occur more frequently)

¶ 98

Leave a comment on paragraph 98 0

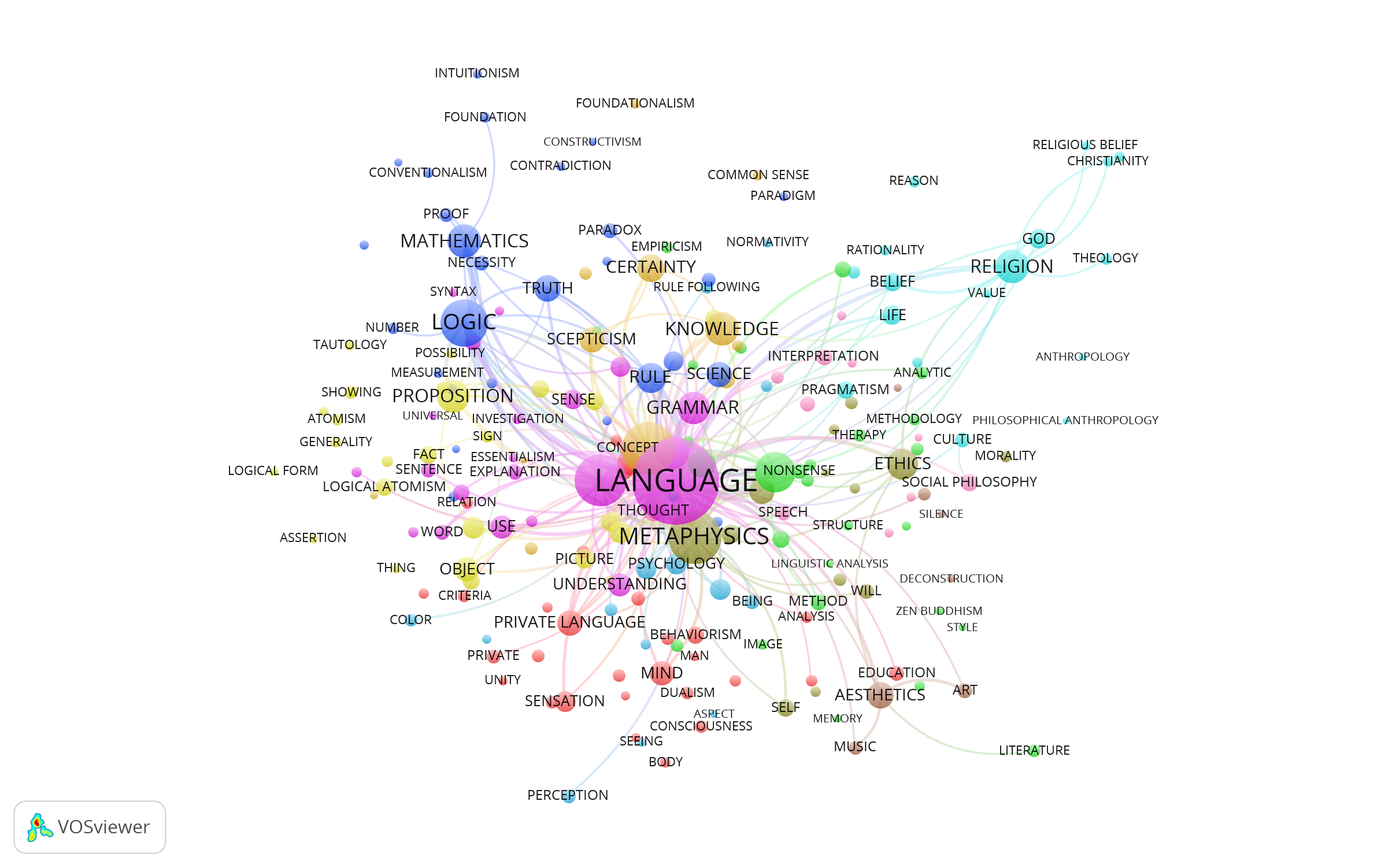

¶ 99 Leave a comment on paragraph 99 0 Fig. 11. A conceptual map of subjects in the literature on Wittgenstein, 1951-2015.

¶ 100 Leave a comment on paragraph 100 0 Legenda: Eleven clusters (colours) for 207 subject items. Size of nodes is contingent upon weight of links (visualized only the strenghtest 200 links). MINIMUM TOTAL LINK STRENGTH OF ANY ITEM = 1.

¶ 101 Leave a comment on paragraph 101 0 As suggested, fig. 11 is a map representing the conceptual structure of Wittgenstein scholarship, the network of concepts and themes he has addressed in his work as it is made available to his readers and scholars. Some clusters are easily identifiable (a Language cluster, a Religion one, a Logico-mathematical, a Psychological, an Aesthetical, etc.). What is more interesting is indeed the network of concepts producing the individual clusters. So we can see that “culture” and even “anthropology” are strongly associated with “religion” and other “theological” subjects, “rule” and “rule followings” is linked with logico-mathematical arguments (cluster blue) and so on. To make things more readable, and possibly easier to decipher according at least to temporalities, we have disaggregated the subject analysis in three time periods, an early one (1951-1970), a middle one (1971-1990) and a contemporary one (1991 to 2015). The results are presented in the three following maps.

¶ 102

Leave a comment on paragraph 102 0

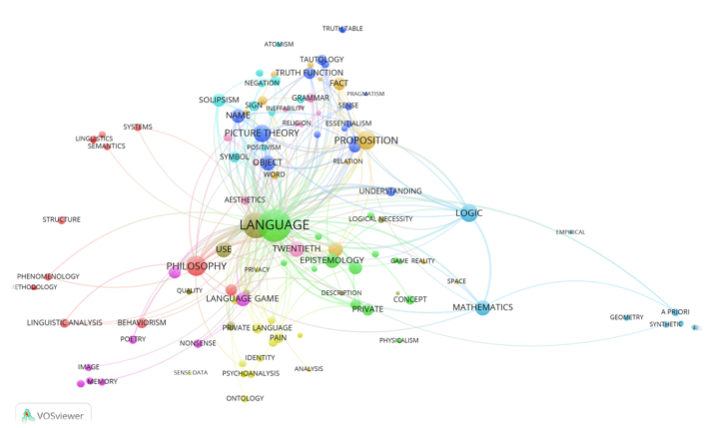

¶ 103 Leave a comment on paragraph 103 0 Fig. 12. A conceptual map of subjects in the literature on Wittgenstein, 1951-1970.

¶ 104 Leave a comment on paragraph 104 0 Note: threshold co-occurrences: 10; minimum cluster size: 5.

¶ 105

Leave a comment on paragraph 105 0

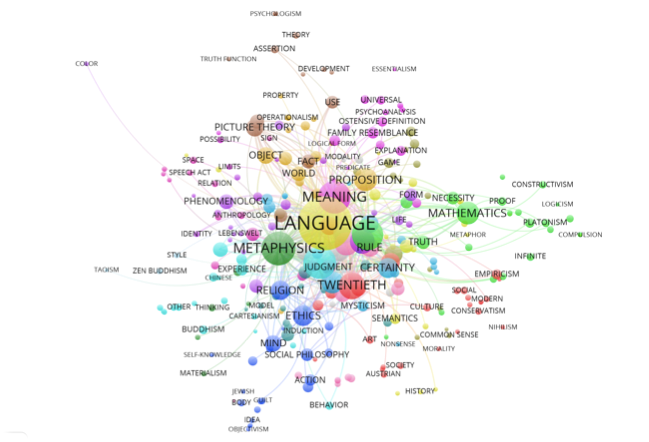

¶ 106 Leave a comment on paragraph 106 0 Fig. 13. A conceptual map of subjects in the literature on Wittgenstein, 1971-1990.

¶ 107

Leave a comment on paragraph 107 0

Note: threshold co-occurrences: 10; minimum cluster size: 5. Links in the map are the stronger 400 ones.

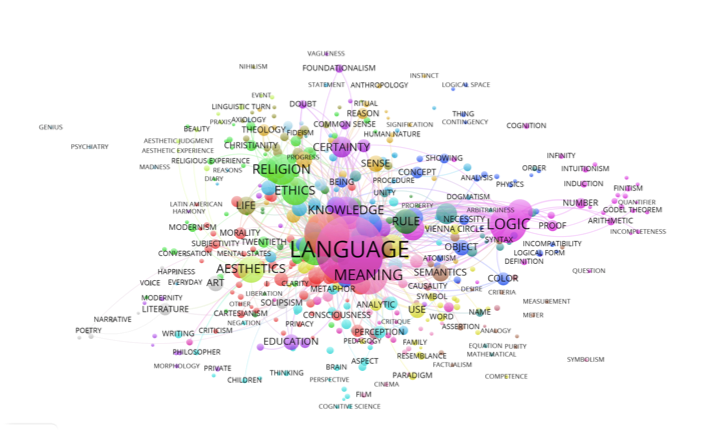

¶ 108 Leave a comment on paragraph 108 0 Fig. 14. A conceptual map of subjects in the literature on Wittgenstein, 1991-2015.

¶ 109 Leave a comment on paragraph 109 0 Note: threshold co-occurrences: 10; minimum cluster size: 5. Links in the map are the stronger 500 ones.

¶ 110 Leave a comment on paragraph 110 1 Comparing the three figures a few elements emerge: a) the persisting centrality of “language” as a subject; b) a pattern of increasing connectivity among the subjects (i.e. a reduction of subjects’ dispersion, still visible in fig. 12); c) the rise of “metaphysics” and “mathematics” as central subjects in the 1971-1990 and their relative decline in the following period; d) a focus shift toward subjects as “ethics,” “aesthetics,” “religion” and “knowledge”[38] in the last period (1991-2015). These are just very first and still impressionistic results we can infer from an inspection of the three maps

¶ 111 Leave a comment on paragraph 111 0 A way to read this series of maps besides looking a their content, is to compare their structural (therefore formal) features, e.g. in terms of the total number of nodes (subjects), and the total number of clusters (subjects’ patterns of association). In the 1951-70 period, these figures were respectively 149 and 10. In the period 1971-90 they were 292 and 18, and finally, in the last period 1991-2015, they were 466 and 20. This means that in those six decades the trend has been toward a growth in both subjects’ number and subjects’ clusters, but also a reduction of the dispersion of subjects across clusters (this means clusters have become more internally articulated and therefore complex with time).

4.3 Modelling topics

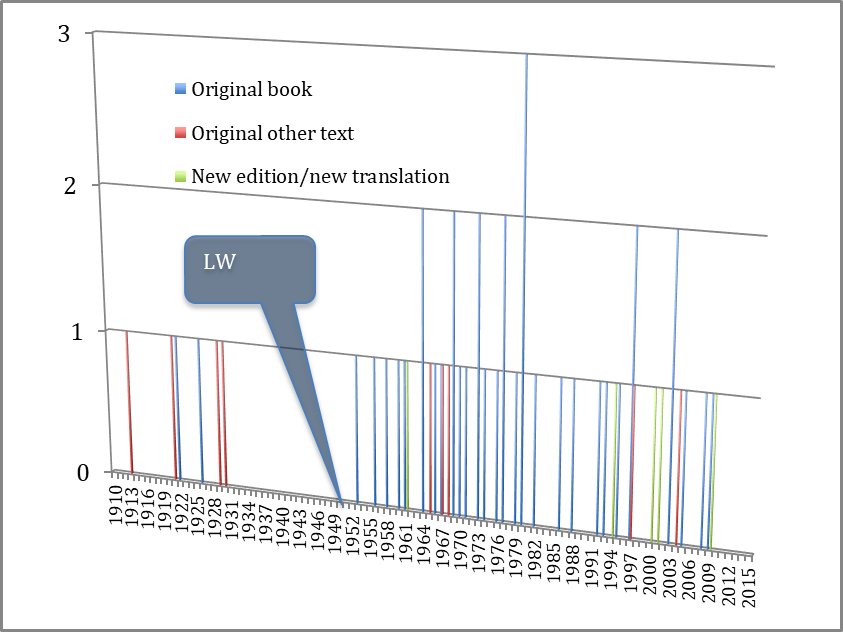

¶ 112 Leave a comment on paragraph 112 0 As anticipated, in order to develop our methodical exploration of the content side of this research field we decided to apply another technique, topic modelling, a statistical technique which allows the fast exploration of large amounts of text data (see Mohr and Bogdanov, 2013). First, we pre-processed our corpus of 1650 abstracts following standard text analysis procedures (see Krippendorff, 2013) – e.g. “stop words” removal and content lemmatization using R library “tm”. Second, we removed generic academic terms frequently occurring regardless of the discipline (e.g. “essay”, “book”, “analysis”), aiming to reduce the “noise” and better highlight the discursive facets of Wittgenstenian scholarship. For this purpose, we employed a customized version of the Academic Word List (Coxhead, 2000), resulting in 2940 terms, and filtered them out together with other frequently occurring and scarcely informative terms in our corpus (e.g. “Wittgenstein”). Third, we selected a 16-topics LDA solution after different attempts (e.g. k=15; 20; 10). By selecting k = 16, we have maximized at the same time the ex-post, qualitative interpretability of the resulting topics (DiMaggio et al., 2013) and the statistical accuracy of the model – verified using R package “ldatuning” (Nikita, 2014). The 16-topic solution has been obtained using R package “topicmodels”, which enabled also the detection of each abstract’s “prevalent” topic. This information has been then used for analyzing the distribution of topics over time (see Figures 15-16). The authors have jointly labelled and interpreted the 16 topics, based on the lists of most associated 300 terms.

¶ 113 Leave a comment on paragraph 113 0 What emerges from this analysis is a) the fragmentation and dispersion of topics, b) their changing weight in time. Which are the topics? From an inspection of data (see Appendix for more subtle information and evidence) we suggest this list of topic labels [with question mark those we have doubts and for which we ask help from historians of philosophy and Wittgenstein’s specialists]:

¶ 114 Leave a comment on paragraph 114 0

¶ 115 Leave a comment on paragraph 115 0 Topic 1 (rules/action)

¶ 116 Leave a comment on paragraph 116 0 Topic 2 (philosophy of mind/psychology)

¶ 117 Leave a comment on paragraph 117 0 Topic 3 (truth or normative?)

¶ 118 Leave a comment on paragraph 118 0 Topic 4 (metaphysics)

¶ 119 Leave a comment on paragraph 119 0 Topic 5 (mathematics)

¶ 120 Leave a comment on paragraph 120 0 Topic 6 (aesthetics)

¶ 121 Leave a comment on paragraph 121 0 Topic 7 (epistemology?)

¶ 122 Leave a comment on paragraph 122 0 Topic 8 (music?)

¶ 123 Leave a comment on paragraph 123 0 Topic 9 (critical publishing history/metaphilosophy)

¶ 124 Leave a comment on paragraph 124 0 Topic 10 (ethics)

¶ 125 Leave a comment on paragraph 125 1 Topic 11 (religion)

¶ 126 Leave a comment on paragraph 126 0 Topic 12 (practice)

¶ 127 Leave a comment on paragraph 127 0 Topic 13 (Tractatus)

¶ 128 Leave a comment on paragraph 128 0 Topic 14 (phenomenology?)

¶ 129 Leave a comment on paragraph 129 0 Topic 15 (language)

¶ 130 Leave a comment on paragraph 130 0 Topic 16 (LW in the history of ideas)

¶ 131 Leave a comment on paragraph 131 0

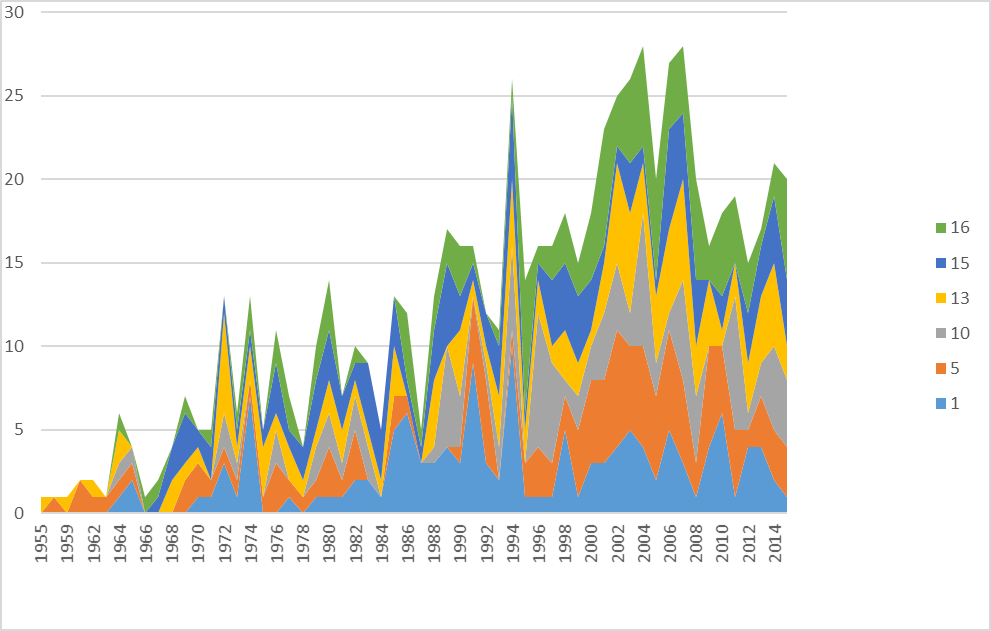

¶ 132 Leave a comment on paragraph 132 0 The three following figures give an idea of these topics’ relative weight and their change over time. Let us say as brief comment on them that heterogeneity booms in the end of 1960s, when the overall number of publications of Wittgenstein in English sharply increases. There seems to be evidence of a relative decline in topics that characterized the very first publications on Wittgenstein (e.g. topic 2, philosophy of psychology, topic 14, phenomenology), while other topics seems constant (e.g. 13 on Tractatus), and new topics are emerging and gaining relative importance: for example, we notice an increasing relevance of rule/action theory (topic 1) and metaphilosophical topics regarding publishing history (topic 9) and historical influence of Wittgensteinian thought (topic 16) (see fig. 17).

¶ 133

Leave a comment on paragraph 133 0

¶ 134 Leave a comment on paragraph 134 0 Fig. 15. Topics, 1951-2015, absolute figures.

¶ 135

Leave a comment on paragraph 135 1

¶ 136 Leave a comment on paragraph 136 0 Fig. 16. Topics, 1951-2015, percentages.

¶ 137 Leave a comment on paragraph 137 0

¶ 138

Leave a comment on paragraph 138 0

¶ 139 Leave a comment on paragraph 139 0 Fig. 17. A zoom on some specific topics of theoretical relevance.

¶ 140 Leave a comment on paragraph 140 0 Aiming to better understand how the structure of the Wittgenstenian field affects publications’ content, we have correlated the number of topics per year and the number of publishing journals per year. For this purpose, we have focused on a subset of 1281 journal articles in English, published in 274 different venues, excluding monographs, PhD dissertations and other types of contributions from the analysis. The correlation between number of journals per year and number of topics per year is, predictably, very high (0.92). Interestingly, it is even higher than the obvious correlation between number of publications per year and number of topics per year (0.90) – which is partly due to the way in which topic models are calculated. The longitudinal distribution of these three variables is presented in Fig. A4 in the Appendix. The strong correlation between number of publishing journals and number of topics appearing in articles about Wittgenstein clearly suggests that the structure of the Wittgenstenian field impacts on its symbolic space.

- ¶ 141 Leave a comment on paragraph 141 0

-

By way of conclusions: Wittgenstein beyond philosophy

¶ 142 Leave a comment on paragraph 142 0 How the structural changes in contents we have detected may be explained from a sociological perspective? Clearly, how much these variations can be accounted for with the changing social structure of the philosophical field and the Wittgenstenian microcosm, i.e. with the social properties of the population of writers on LW, is the central question a sociological reading of Wittgenstein’s legacy and his trajectory in time/space (including “analytic philosophy as a tradition” partly derived from the latter) should address. This is indeed the final question of our research, even if at present we have to limit ourselves to just a few hypothetical constructions[39].

¶ 143 Leave a comment on paragraph 143 0 Let us distinguish them in two classes: exogenous and endogenous (hypothetical) explanations. The first class comprises all those sociological approaches that try to make sense of variations in cultural systems through a focus on elements not immediately belonging to the culture sphere as market structures, institutional arrangements and socio-structural boundaries. Variations in cultural and symbolic systems are conceived as contingent upon variations in institutional systems. This first class of approaches, long dominant in the sociology of culture (see Crane 1992; Griswold 1995; Santoro 2008; Santoro and Solaroli 2016), has been more recently supplemented by a series of approaches insisting on endogenous explanation of cultural life. By this we could mean

¶ 144 Leave a comment on paragraph 144 0 that the sociological approach to culture has of late backed away from a style of reasoning that presumes to explain culture through extra-cultural factors such as social structure (DiMaggio 1982), the economics of artistic production (Peterson 1976), the institutional makeup of criticism and dissemination of the arts (Griswold 1987), and so forth. Endogenous explanations focus instead on causal processes that occur within the cultural stream: mechanisms such as iteration, modulation, and differentiation, as well as processes such as meaning making, network building, and semiotic manipulation. This new approach has merit in that it makes culture more than just a dependent variable (Kaufman 2004, 336).

¶ 145 Leave a comment on paragraph 145 0 Having clarified this distinction (but see infra for a further discussion on this point), we can speculate about at least four tentative ways of accounting for the structure and transformation of Wittgenstein’s scholarship. Take the following as thought experiments, or better, as speculations about future research directions. We start with exogenous explanations, and specifically with the following one:

¶ 146 Leave a comment on paragraph 146 0 H1: the changing topical structure i.e. volume and relative weight of topics, is homological (that is, corresponds) to a changing social structure in the Wittgenstenian microcosm as a subregion of the philosophical establishment (discipline).

¶ 147 Leave a comment on paragraph 147 0 To elaborate further on this hypothesis we would need more data on the social properties of the Wittgenstenians i.e. the population of writers on LW (as operatively defined in our study), including the social arrangements of their collaborations, modes of recruitment, modes of recognition, international circulation of texts (papers, articles, books, including translations) and so on. This would ask also for an investigation of the changing institutional environment in which these scholars have been working: the creation of specialised journals, the launch of book series, the founding of societies and associations as the Austrian Ludwig Wittgenstein Society (ALWS), active since 1974, the North American Wittgenstein Society (since 2000), the British Wittgenstein Society (BWS) and the Nordic Wittgenstein Society (both since 2008), periodic congresses, and the establishment of scholarly institutions as the Wittgenstein Archives at the universities of Cambridge and of Bergen (WAB).[40]. These and similar arrangements or devices are just the most visible and active institutions or organizations embedded in what we have named the Wittgensteinian field – indeed, they make up the institutional environment where research work on LW occurs.

¶ 148 Leave a comment on paragraph 148 0 This first research line would be firmly grounded in the traditions of the sociology of knowledge and of science (including their more recent development as “the new sociology of ideas” [see Camic and Gross 2001]), and would amount in the end to a story of formation and increasing institutionalization of a specialised research field, with all the implications this social process may have on intellectual and academic life, e.g. competition, conflict, patterns of alliance, spatial concentration of creativity, and so on (see e.g. Mullins 1972).

¶ 149 Leave a comment on paragraph 149 0 A second hypothesis is imaginable at this point:

¶ 150 Leave a comment on paragraph 150 0 H2: the changing topical structure is a consequence of wider changes in intellectual fields, which go beyond the philosophical field and the more specialised microcosm of the Wittgenstenian scholarship.

¶ 151 Leave a comment on paragraph 151 0 This second hypothesis asks for a wider research frame, capable to capture structure and transformations in circles and microcosms, i.e. in fields, larger than philosophy as a discipline or even as a federation of research groups. Recall what we said at the very beginning of this paper: as sociologists we have been interested in researching on LW also because of his influence on our discipline. But sociology is just one of the disciplines influenced by Wittgenstein’s ideas in the past fifty years (see e.g. on theology Kerr 2005; on anthropology Das 1998; on biology Baquero & Moya 2012; on the social sciences more in general see Hughes 1977). In order to assess the spread and development of LW’s ideas and writings it is apparent we cannot limit ourselves to what happens in the field of philosophy. At least, this would misrepresent what Wittgenstein is todays, what his name means in intellectual life even beyond disciplinary boundaries. In a sense, this is the main point when discussing LW: is he only a philosopher or not? Or maybe, better: is philosophy nowadays something different from what philosophy was at the time of Wittgenstein? Can it be that the declining place of LW in contemporary philosophy is the effect of a transformation of philosophy in a direction that LW not only preconized but also fought, i.e. its professionalization? [41]

¶ 152 Leave a comment on paragraph 152 0 As we can read in a popular web source on philosophy (representative, we could say, of the common wisdom in the discipline): “[his] style of doing philosophy has fallen somewhat out of favor, but Wittgenstein’s work on rule-following and private language is still considered important, and his later philosophy is influential in a growing number of fields outside philosophy” (from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy-IEP). In other words, “forgetting Wittgenstein” (Tripodi 2009) may not be the right slogan for capturing what is occurring in scholarship and more in general in the intellectual debate when you look at what happens in other fields than philosophy.

¶ 153 Leave a comment on paragraph 153 0 Unfortunately, our main archive is specialized exactly in this field so it can be very useful for us. An alternative source of data – one we are also working upon – is the more general and highly reputed Web of Science (WoS) founded in the fifties by Eugene Garfield (one of the pioneer in bibliometric studies) and nowadays managed by Thompon-Reuters.[42]

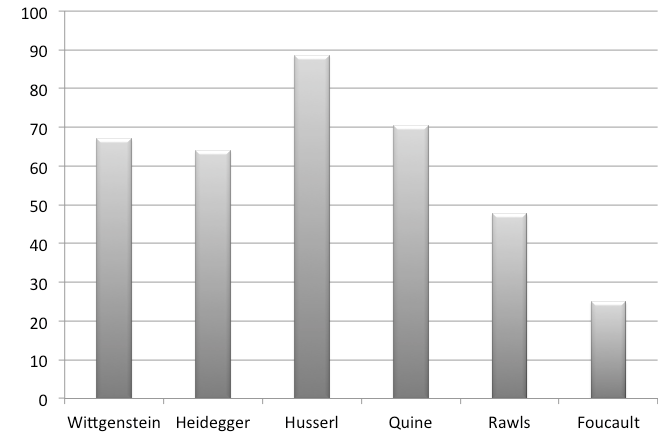

¶ 154 Leave a comment on paragraph 154 1 We therefore did with WoS the same we did with PI, i.e. selected records (= publications indexed in one of the various databases maintained by Thompson-Reuters) containing the tag “Wittgenstein” in the title. The total dataset comprises 3136 records, which we have analyzed with the standard tools WoS makes available to its users. In particular, we explored the distribution of these records by Research Area (an information the indexing service of WoS provides). The results of our exploration confirm that LW has a place also out of the borders of philosophy as a disciplinary endeavor, but also that philosophy (accounting for 67% of the occurrences[43]) is possibly still the most important place where LW’s ideas are debated – which is not the same as saying that it is the most important place where they circulate (see fig. 18 for a comparison with other XX century philosophers we selected as benchmarks). We have indeed to acknowledge that Wittgenstein is still a central presence in the philosophical field more than in other fields – his presence in research areas different from philosophy is minor than that of Rawls and Foucault, even if more than that of Husserl. It doesn’t seem to be differences among LW and Quine or even Heidegger. However, it can still be the case that LW’s ideas have an impact in intellectual debates different from the strictly philosophical ones, but that these ideas are not directly discussed and don’t constitute the reference topic of publications: in other terms, they are more resources than objects of discussion.[44]

¶ 155

Leave a comment on paragraph 155 0

¶ 156 Leave a comment on paragraph 156 0 Fig. 18. Publications on selected XX century philosophers with “Philosophy” as Research Area (% on total publications for each philosopher), 1985-2015. Source: WoS.

¶ 157 Leave a comment on paragraph 157 0 After this couple of explanatory hypothesis which emphasize external i.e. exogenous forces, let’s now suggest two endogenous explanations. We would distinguish them as they ask for different research strategies and sources.

¶ 158 Leave a comment on paragraph 158 0 H3. Variations in time and space in LW’s scholarship, including variations in topics and their relative weight, are contingent upon processes of symbolic production of value, especially in terms of reputation-building and consecration.

¶ 159 Leave a comment on paragraph 159 0 LW is possibly one of the most celebrated scholars of our days. His fame goes well beyond the kind of recognition philosophers usually gain. In the following excerpts the reader can find few exemplary statements about the curious and for some verses ambivalent place LW occupies in philosophy, according to various disciplinary sources.

¶ 160 Leave a comment on paragraph 160 0 Ludwig Wittgenstein occupies a unique place in twentieth century philosophy and he is for that reason difficult to subsume under the usual philosophical categories. What makes it difficult is first of all the unconventional cast of his mind, the radical nature of his philosophical proposals, and the experimental form he gave to their expression. The difficulty is magnified because he came to philosophy under complex conditions which make it plausible for some interpreters to connect him with Frege, Russell, and Moore, with the Vienna Circle, Oxford Language Philosophy, and the analytic tradition in philosophy as a whole, while others bring him together with Schopenhauer or Kierkegaard, with Derrida, Zen Buddhism, or avant-garde art. Add to this a culturally resonant background, an atypical life (at least for a modern philosopher), and a forceful yet troubled personality and the difficulty is complete. To some he may appear primarily as a technical philosopher, but to others he will be first and foremost an intriguing biographical subject, a cultural icon, or an exemplary figure in the intellectual life of the century. Our fascination with Wittgenstein is, so it seems, a function of our bewilderment over who he really is and what his work stands for (Hans Sluga, Introduction to Cambridge Companion to W, 1996).

¶ 161 Leave a comment on paragraph 161 0 Although Wittgenstein is widely regarded as one of the most important and influential philosophers of this century, there is very little agreement about the nature of his contribution. In fact, one of the most striking characteristics of the secondary literature on Wittgenstein is the overwhelming lack of agreement about what he believed and why. Over forty years after his death, despite the publication of over a dozen books from his Nachlass (the usual term for his unpublished papers), hundreds of books on his work, and thousands of scholarly articles, his philosophy remains unavailable to many of his readers. In part, that is because Wittgenstein’s writing asks for a change in sensibility that many of his readers are unwilling or unable to accept. The continuing unavailability of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is also due, in large part, to the expectations of those interpreters who disregard his way of writing, looking for an underlying theory they can attribute to him (DAVID G. STERN, The availability of Wittgenstein’s philosophy, ibidem, p. 442).

¶ 162 Leave a comment on paragraph 162 0 Wittgenstein is a contested figure on the philosophical scene. Having played an important role in the rise and development of not just one but two schools of analytic philosophy – one that emphasizes the use of formal logical tools in philosophical analysis, originating with Bertrand Russell, and one that sticks, more or less, to the use of everyday language in philosophy, connected also with the name of G. E. Moore – he is for good reasons associated with the analytic tradition. Nevertheless, Wittgenstein’s relation to (what we now call) analytic philosophy tended to be somewhat uneasy. While both Russell and Moore describe the young Wittgenstein as a genius in philosophy and logic, Wittgenstein himself thought they failed to understand his work in certain crucial respects. […] In contemporary analytic philosophy, by contrast to its earlier phases, Wittgenstein tends to play a less central role. There are, of course, figures deeply influenced by Wittgenstein – such as Robert Brandom, Stanley Cavell, Cora Diamond, John McDowell, Barry Stroud, Charles Travis, and Crispin Wright. Wittgenstein scholarship is also actively pursued in many philosophy departments, resulting in several new books every year. Nevertheless, the philosophical climate has clearly changed since the heyday of Wittgenstein’s influence. Metaphysics – which Wittgenstein argued to involve a conflation of factual and logical statements – is again regarded as a respectable undertaking among analytic philosophers, and generally current trends favour the idea that philosophy should be understood and pursued as a science – an idea Wittgenstein was highly critical of throughout his career (Editors’ Introduction, in The Oxford Handbook of Wittgenstein, edited by Oskari Kuusela and Marie McGinn, Oxford UP 2011.)

¶ 163 Leave a comment on paragraph 163 0 Considered by some to be the greatest philosopher of the 20th century, Ludwig Wittgenstein played a central, if controversial, role in 20th-century analytic philosophy. He continues to influence current philosophical thought in topics as diverse as logic and language, perception and intention, ethics and religion, aesthetics and culture. Originally, there were two commonly recognized stages of Wittgenstein’s thought—the early and the later—both of which were taken to be pivotal in their respective periods. In more recent scholarship, this division has been questioned: some interpreters have claimed a unity between all stages of his thought, while others talk of a more nuanced division, adding stages such as the middle Wittgenstein and the third Wittgenstein. Still, it is commonly acknowledged that the early Wittgenstein is epitomized in his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. By showing the application of modern logic to metaphysics, via language, he provided new insights into the relations between world, thought and language and thereby into the nature of philosophy. It is the later Wittgenstein, mostly recognized in the Philosophical Investigations, who took the more revolutionary step in critiquing all of traditional philosophy including its climax in his own early work. The nature of his new philosophy is heralded as anti-systematic through and through, yet still conducive to genuine philosophical understanding of traditional problems (SEP, First published Fri Nov 8, 2002; substantive revision Mon Mar 3, 2014).

¶ 164 Leave a comment on paragraph 164 0 Ludwig Wittgenstein is one of the most influential philosophers of the twentieth century, and regarded by some as the most important since Immanuel Kant. His early work was influenced by that of Arthur Schopenhauer and, especially, by his teacher Bertrand Russell and by Gottlob Frege, who became something of a friend. This work culminated in the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, the only philosophy book that Wittgenstein published during his lifetime. It claimed to solve all the major problems of philosophy and was held in especially high esteem by the anti-metaphysical logical positivists. The Tractatus is based on the idea that philosophical problems arise from misunderstandings of the logic of language, and it tries to show what this logic is. Wittgenstein’s later work, principally his Philosophical Investigations, shares this concern with logic and language, but takes a different, less technical, approach to philosophical problems. This book helped to inspire so-called ordinary language philosophy. This style of doing philosophy has fallen somewhat out of favor, but Wittgenstein’s work on rule-following and private language is still considered important, and his later philosophy is influential in a growing number of fields outside philosophy. (from The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy (IEP)available at the address http://www.iep.utm.edu/wittgens/#SH11a).

¶ 166 Leave a comment on paragraph 166 0 Yes, as sociologists we hold these results and set forth an explanatory hypothesis for this ranking and more in general the ambivalent status of LW among philosophers – high and contested at the same time: we may consider it as a consequence of the difficult reputation LW has enjoyed since his early years as a would be author (of the curious, atypical text later published as the Tractatus) and after a few years as a PhD student and professor at Cambridge, a process starting with Bertrand Russell’s intellectual infatuation for his supposed, presumed exceptional talent, and continued in the following decades through the intensive symbolic work done around LW’s persona by a few influential colleagues, a group of his early students, some students of his students (see Gellner 1998a, 1998b), and a growing body of more or less personally distant scholars who have been writing about him, including of course his biographers (from Norman Malcolm [1958] to Ray Monk, whose 1990 book on LW “as genius” has played an influential role in rising LW’s status among younger generations of philosophers).

¶ 167 Leave a comment on paragraph 167 0 This is very simply what sociologists define as a “process of reputation-building” or even – when especially successful in establishing a name and her value – of “consecration” (e.g. Heinich 1997; DeNora 1995; Bourdieu 1992; Fine 2000; Kapsis 1992; Santoro 2010; Bartmanski 2012), a process that is at the same time social and cultural: social because you need social agents and social institutions to consecrate, i.e. to build the recognition of an exceptional status of someone; cultural because you can do this with success only through an able play of signifiers and meanings, and with large amount of symbolic work in form of critical reviews, biographical texts, discussions of ideas, and so on.

¶ 168 Leave a comment on paragraph 168 0 This brings us to our fourth and last hypothetical explanation, the most elemental maybe, but not exactly the preferred one from a sociological perspective because of its apparent distance from social structure. We can elucidate it in this way: